In 1941 the prominent American architect Wallace Neff was shaving his face. Standing at the bathroom sink in one of the grand Spanish Colonial homes for which had garnered him immense popularity and created his name as an architect Ness’ eye was drawn to a bubble of soap. It was from this bubble – produced from the sudsy lather on his face – that an idea Ness considered to be the highlight of his illustrious career was born. Bubble houses.

The spark of inspiration the designer found in this bubble of soap was an incident set against a backdrop of a revolutionary design movement that would define the 20th century: Modernism. The movement which would see its peak from the 1930s to early 1960s was defined by the abandonment of unnecessary ornamentation and an emphasis on the design of form purely as a tool of function. This shift in design, evident across an array of so-called ‘Western’ art forms was emblematic of dramatic socio-economic changes including increasing industrialization and rapid population growth. By the 1940s sleek lines and a relationship with the natural world were defining features of popular architecture.

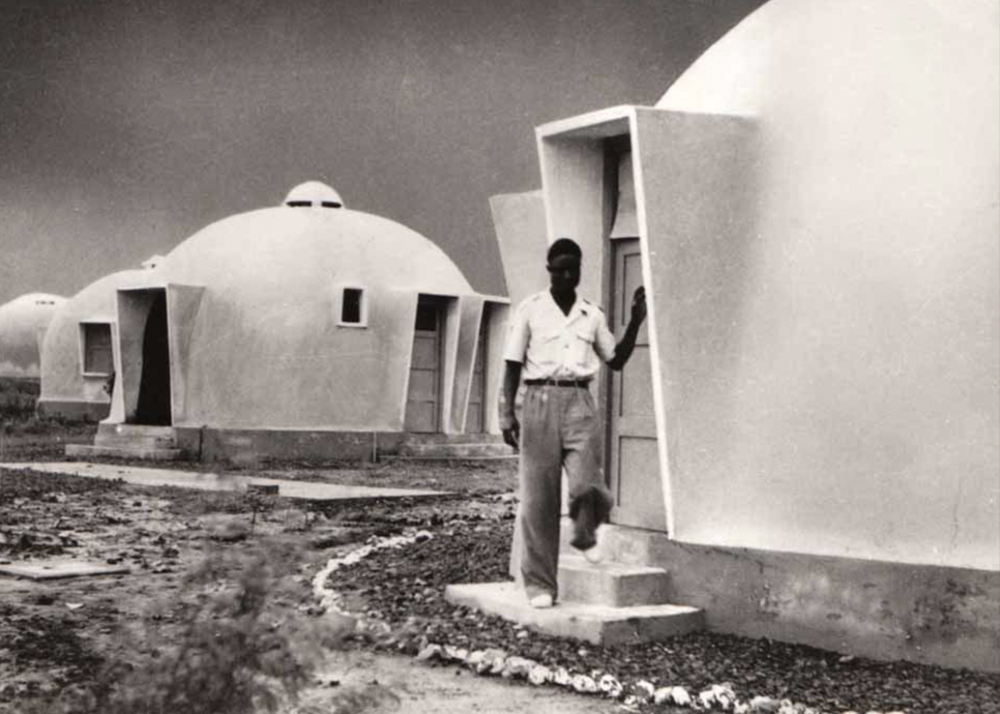

In a dramatic departure from his architectural roots, Neff developed a revolutionary design known as ‘air forms’ or more colloquially as ‘bubble houses’. These structures which are visually striking for their geodesic shape were most revolutionary for the viable solution they offered to the housing crisis anticipated in America following World War II. Bubble houses could be constructed by two men in under 48 hours and required few materials besides a large inflatable balloon and a sprayable mixture of water and dry cement known as gunite. Once the mixture had dried the bubble could be deflated and removed via the front door and thus could be reused to build yet another domed structure.

Ness, who had previously worked as an architect for the lavish homes of celebrities such as Charlie Chaplin and Judy Garland asserted his view of this project as his social responsibility. Like other architects following the tenets of modernism Ness’s bubble houses prioritized function as they were remarkably easy to build and highly durable against fire, earthquakes and wind. However, the strikingly minimalist and unconventional form of these houses would result in their inevitable failure to take hold in Western society: too unusual and modest in appearance, the structures could not compete with the rise of more sizeable ‘picture perfect’ single-family houses that defined the development of suburban sprawl in the post-war years. While some of Ness’s homes still stand in countries such as Senegal, Pakistan, and South Africa only one remains In North America, Ness’s former personal home in Pasadena California.

The failed project of the air form or bubble house is emblematic of the failure in North America of the urban utopia of the early 20th century. The vision of the modernists was one of a society whose architecture reflected a concern with function over form, and one wherein emphasis is placed on the importance of urbanization for the betterment of humanity. Today many modernist structures like the bubble houses or Montreal’s famous Habitat 67 are imbued with a sense of liminality. Scarce in numbers, these structures feel caught between an identity as relics of a naïve and somewhat antiquated view of the world and simultaneously as though they are – still 80 years later – on the precipice of a revolutionary way of living. That feeling of modernist spaces as being an unsettling site of transition between past and future is effectively described by artist and owner of the last American bubble house Steve Roden, who stated that “looking at the house which resembles a smooth mound of earth it feels as if some ancient space station has fallen from the sky and upon landing has embedded itself into the wrong context.”

Indeed, the brief optimistic flicker of an idealized way of living that the modernists envisioned was largely extinguished in the latter half of the 20th century as members of the North American middle class rejected – for better or worse – more utilitarian modes of living for homes which provided greater comforts and acted as more conspicuous class symbols. While elements of modernism are still hugely impactful in contemporary design, many products of a movement that sought to revolutionize societal function feel caught in the past. Whether in the form of brutalism or bubble houses, modernist structures act as liminal spaces between 20th-century visions for the future and contemporary realities.

Kate is an Editorial Intern at liminul.

She is a writer, photographer, and graphic designer based in Montreal. Kate is currently in her final year of her B.A. at McGill University where she is double majoring in history and art history.