“I think I was really craving something a little bit more like banging my head against a wall without me actually doing it,” Chloe Majenta tells me. In an interview with Liminul, Majenta, a multidisciplinary artist based in Montreal and originally from rural British Columbia, sat to discuss her recent series of paintings titled “Enantiodromia.” Over the past year, Majenta created twelve paintings for artch Montreal as a part of their 2024 cohort of emerging artists. Inspired from the Greek word enantios, which means “opposite,” the title of Majenta’s series came from a studious pursuit of what psychologist Carl Jung popularly defined as “the principle that everything eventually makes way for its opposite.”

Majenta started work on Enantiodromia after taking an interest in professional boxing. “[Boxing] really feels like a vessel for a lot of human troubles that we’re experiencing,” she says, “and we can channel that fear and frustration into the boxers.” In watching two men stripped to their waists pound their fists into each other, Majenta sensed a distinct, sweet discharge of tension in herself as well as the men fighting.

As a naturalist painter of a realist style, Majenta draws inspiration from 17th-century Dutch still life. In Enantiodromia, she turns this gaze to professional boxing and the spectacle of the blood sport to suggest what lies beneath it all. With a nod to painter George Bellows’ gritty depictions of early 20th-century American prizefights, Enantiodromia questions the social nature of the archetypal fight, albeit from a subtle, more esoteric standpoint. Where Bellows leaned into the raw physicality of the ring with snapshots of roused crowds and full-bodied men in an attempt to capture the wild, bristling energy of American masculinity, the artist works with overarching archetypes, zooming in close to observe her fighters in moments of intimate engagement before reaching far outside the ring into the cosmos that ordered them. She remains esoteric, layering her compositions with mythological and tarot symbolism and increasing the ring into more than a playground to contemplate the unholy affair between the ideals of war and beauty themselves.

In a series of five fight scenes painted from real-life boxing matches, Majenta creates close-up freeze-frames of moments of impact. In fights two and five, men’s faces ripple from the force of a well-aimed punch. In Fight 2, a man’s mouth opens to expose a white mouth guard. In Fight 5, the mouth guard is gone, and a Black man’s obliterated face splashes cherry red blood as a thick, creamy-white string of saliva flies from his mouth.

Despite a clear infliction of terrible pain in the painting, Majenta renders it in the gentlest brush strokes over layers of sand and gesso on smooth wood panel. Zooming in on these anonymous men with tender textures on a hard, smooth surface, Majenta infuses the fight scene with a charged sensual and sexual undercurrent. The boxers’ tight, scrunched up faces hearken back to photographer Peter Hujar’s Orgasmic Man, 1969 and painter George Benjamin Luks’ The Wrestlers, 1905; that vulnerable, ambiguous expression of men caught between suffering and primal ecstasy. From fights one through five, I also sense a narrative building up, tension and action rising from the first punch thrown to the final shocking ejection of blood that ends the match.

Through Majenta’s gaze — which mirrors that of the spectator — this blood bursts out with the pressure and pleasure of a mighty ejaculation. On one level, the boxing match becomes a perverse, pornographic theatre where boxers perform violence for money that, like the performance of sex for money, ends after the moment of purest rapture. The idea of exploitation appears here, and Majenta challenges us to think about the obscenity of capitalist society ritualizing violence as a commodity for mass consumption, much like commodifying and exploiting sex for mass consumption as pornography is obscene. On another level, however, the fight also becomes a conduit to the sublime, wherein self-destruction becomes ascetic practice, and both boxers and spectators transcend material reality to experience true tranquility, annihilating their very sense of self through the physical blows exchanged in the ring.

If nothing else, Enantiodromia emphasizes the intimacy of bodily touch par excellence. In The Lovers, Majenta paints two Black men locked in the heat of a boxing match, set against a pale blue sky with soft white clouds. Inside the borders of the painting, the men are framed within a checkered layout topped with the Roman numerals “VI”— a clear reference to the tarot lovers card — positioned between two black panther-like creatures. The image is at once sacred, beautiful, and unsettling. Through the violence of the fight, Majenta reminds us that hard or soft, rough or tender, touch is still touch, and these men, in some way, enjoy touching each other. In the framing of the tarot card, the need for touch, for violence as a substitute for intimacy, imposes itself as a necessity in the cosmic order.

This intimacy, however, only justifiably exists within the rigid framework of traditional masculinity, where to be deemed acceptable, physical contact between men must be mediated by competition, aggression, or structured rules. Even if it hurts them or makes them bleed, boxing allows men to touch one another in a socially sanctioned way, to abstractly masturbate to and with each other’s bodies, deriving pleasure from it under the noble guise of sport. “There’s a homoerotic energy that is shared, I think, between the fighters, but also between the audience and the fight,” Majenta notes, making explicit the underlying desire that seethes beneath the spectacle of male-male aggression.

Majenta’s paintings here evoke Sigmund Freud’s theory of sublimation, which argues for “undifferentiated sexual dispositions” to be suppressed or redirected toward higher, socially acceptable aims to prevent an outbreak of social perversion. Freud suggests sublimation as the engine behind our greatest cultural achievements. See the institutionalization of marriage and courting rules, which channelled unregulated sexual impulses into the foundation of civil society. See also the invention of sports and games, particularly the bloody contact sports, which paradoxically neutralized the dual grotesquery of same-sex intimacy and the latent human appetite for destruction by sanctioning both through controlled, ritualized violence.

Majenta’s Fight 3 distills this idea with striking clarity. It captures two men locked in a maneuver called ‘the clinch,’ in which fighters physically engage in close-range grappling to neutralize each other’s attacks. In Majenta’s hands, however, the clinch becomes more than a tactical move. Beneath its ruggedness exists an unsophisticated yet warm embrace, a moment of tender yet brutally abstract mutual support—one that would otherwise be forbidden beyond the realm of the ring. “There is so much trust involved [in boxing] and so much respect,” Majenta reflects. “It’s different from a bar brawl… one is respectable, the other is animalic.” Interestingly, the distinction between nobility and animality is only a cultural framing.

Enantiodromia exposes how rules and legal structures frame chaos and destruction into respectable rites through sublimation. Even more striking is the implicit argument for the boxing match to retain a touch of the original brutality it seeks to contain for sublimation to be successful. Similarly, diverting the homo-erotic nature of man does not eliminate it but rather reorients it as violence and play. This logic extends beyond the fight itself into the gendered dimensions of combat sports, which Majenta’s High Priestess of the Bikini observes in the presence of the ‘ring girl’ sexualized as a stabilizing, ornamental figure beside the referee, without whom the dignified ritual of two men punching each other would turn shamefully obscene, and obscenely erotic. In the painting, the girl holds up a sign that says “Round 2” in Roman numerals, a subtle gesture to the dual archetypes of war and beauty bound by eros that govern these spectacles of violence, and the necessary but invisible scaffolding that gives combat its meaning, turning violence into an important ritual, and scandalous desire into something socially permissible.

As such, Ares and Aphrodite, the cosmic entities of war and beauty, remain suggested throughout the scenes and landscapes of Enantiodromia. Majenta raises questions about the beauty of war, what it means for beauty and war to be attracted to each other, and the need for cultural framing to mitigate their depraved connection.

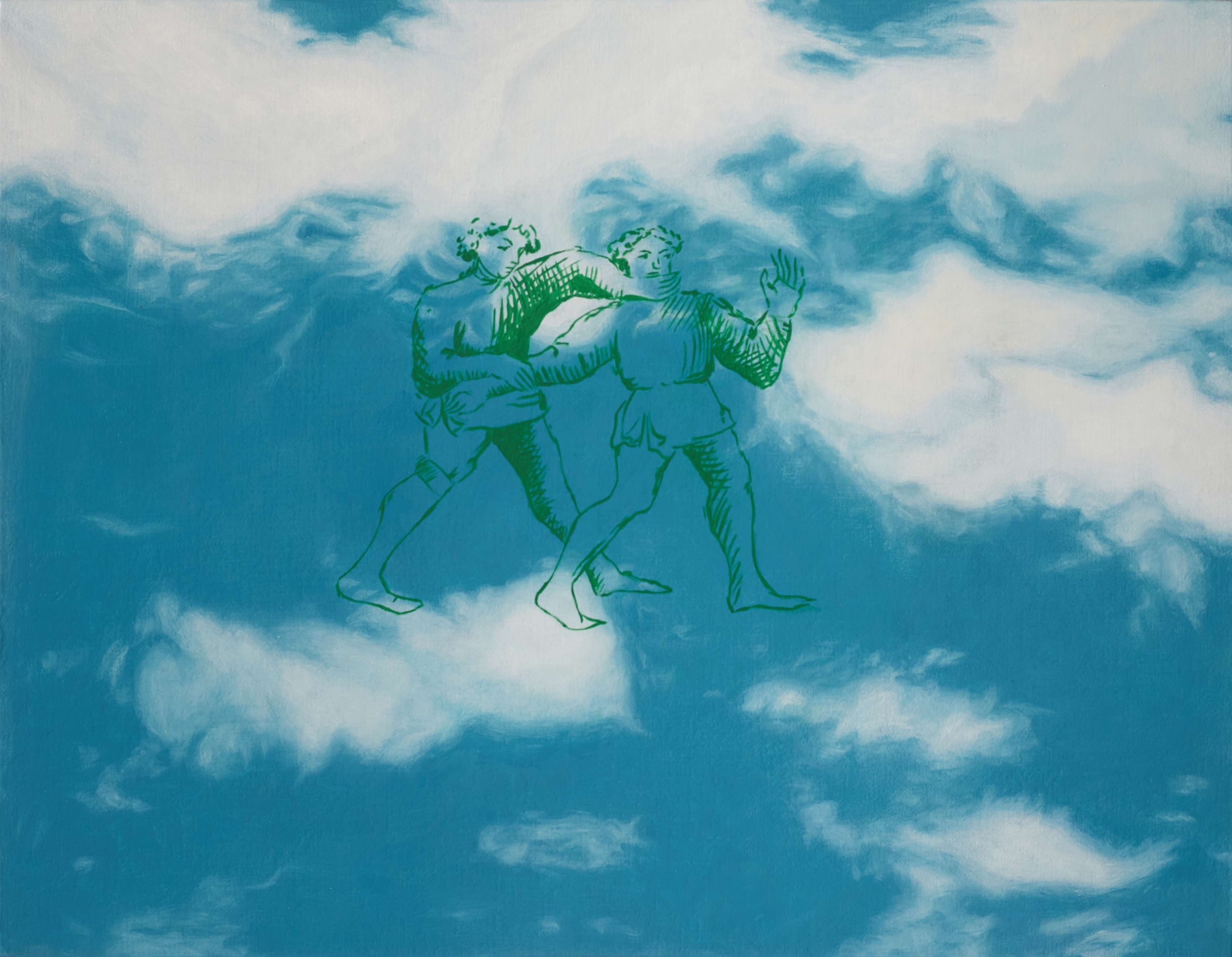

In a painting titled The Wrestlers, Majenta presents two abstract figures who don’t appear to be wrestling but rather floating and playing in a sky peppered by wispy cumulus clouds. Inspired by medieval tarot practise and the sun card, which commonly featured a pair of children wrestling in castle grounds or young jousters in battle practice, the wrestlers become the immortal archetype of every fight; the origin and standard from which every fight thereafter follows, and which every fight in its moment returns to. Again, we encounter the sublime in the terrible and violence as beautiful and natural. The painting appears to refract Luks’ wrestlers, too, and in this abstraction against the clear sky, we glimpse their shared understanding of the sublime and the tranquility that occurs within a moment of adrenaline-driven, sweat-soaked passion.

To wrestle and be wrestled with, the painting posits, means transcending the limits of the human body and being set free, ecstatically. Yes, it may be beautiful, but against the physical destruction of the fight, Majenta does not let the idea of beauty become synonymous with goodness or morality.

With the addition of a painting titled The Sun, Majenta fully abstracts the myth of Ares and Aphrodite’s affair as spied on by the sun god, Helios. From the tarot tradition, Majenta’s sun reintroduces sublimation accompanied by compassion and the triumph of truth (sex) over the playground illusion of the game.

In the painting Children of the Sun, two women wrestle each other in a completely monochromed scene. Majenta acknowledges that from her experience spectating lesbian oil-wrestling in Montreal, “some of them are actually fighting, but most of them are just very sexy.” It is the only instance of the non-male body in the series and the only one rendered in monochrome. The women are dressed casually, unlike other fighters, as though in this honest state of engaged sex, they do not require all the varnish and artifice of colour and costume.

Finally, Enantiodromia makes a case for an authentic and conscious application of violence, sex, and play. Without the pressure to succumb to an archetype of the fight, we can make the archetype serve our own interests, sublimating societal structures for our primal pleasure rather than the other way around for collective entertainment. Here, we may enter the sublime intentionally and consciously. Though one might feel that Majenta needed to further visually explore why non-male-identifying people and non-heterosexual men may fight each other and how, she lays these archetypes down to ask the only important questions: What is left to sublimate if you choose to live as you are? What happens to us then?

Jonathan Divine Angubua is currently finishing his undergraduate studies at the University of Toronto. He enjoys any interesting art and is always looking for great book recommendations. As a writer and lover of fashion, he is most inspired by strangeness and beauty.

Jonathan Divine Angubua is currently finishing his undergraduate studies at the University of Toronto. He enjoys any interesting art and is always looking for great book recommendations. As a writer and lover of fashion, he is most inspired by strangeness and beauty.