Samuel Arsenault-Brassard is a virtual architect and artist living and working in Montreal. His work, some of which is currently exhibited at Montreal’s ELLEPHANT gallery explores light, shadow and form all through the use of virtual reality technology. In addition to his work for ELLEPHANT, Arsenault-Brassard has recently collaborated with buried deep, and Lignes de Fuite on a digitally generated fashion photo series. We spoke with the artist about his prolific career and his passion for all things VR.

How did your interest in VR and Architecture begin?

My interest in architecture stems from my young days as an artist not wanting to struggle financially. By designing buildings, I could create large pieces of art that would withstand the test of time.

After many years of art, architecture school, dropping out and going back to school, I found out that there was a VR headset that was basically “good enough”, the Oculus DK2. I purchased it and started exploring and presenting my architectural projects in VR and became an expert on everything related to VR architecture and art.

After university, I got a job at an architecture & VR startup, so this gave me the opportunity to play with the latest equipment and do some research and development in many different fields: 3D scanning, visualization, lighting, geometry optimization, etc. This research always intersects with my artistic digital projects and vice versa.

You work in digital architecture which is still a developing field. How would you explain the concept of digital architecture to someone who is unfamiliar with it?

VR and AR allow us to create and embody synthetic spaces. Much like the internet, we can imagine a future where major designers and brands have spaces that people can visit and inhabit. We can already do this today and it will only get easier.

This represents a huge shift in the history of art and architecture, a completely new chapter. Therefore, we should not try to recreate what worked before, we have to look at this medium in a radical and transformative manner, to use the new freedoms it grants us and explore these new ways of being in space and experiencing reality.

The role of a VR architect is multifold. It’s important that there is a sensibility to the history of architecture, its traditional languages relating to gravity, its ability to create functionality, comfort and even sensuality.

At one extreme, we could recreate reality as is, focusing on historical architecture and known languages. Normal looking doors, stairs, columns, roofing systems. At the other end, we could design for a post-physical world where the user is simply a mind without traditional limbs, a soul floating through the ether. The balance is a moving spectrum between both terrains, where we design to make humans comfortable with analogies to reality but think way beyond the current limitations of physical design.

There’s also going to be lots of new types of spaces, lots of exciting problems to be solved. Some spaces that could not exist before, for example, what would it feel like to walk through a magazine? Through a poem? What does a VR or AR fashion show look like? What does a cemetery look like in VR? An entertainment venue? A sports stadium? A music video? A concert?

One way of describing the metaverse is to try to imagine what the internet would look like if it was a series of spaces we can inhabit. It won’t just be spaces we can inhabit, but also environments that react to us.

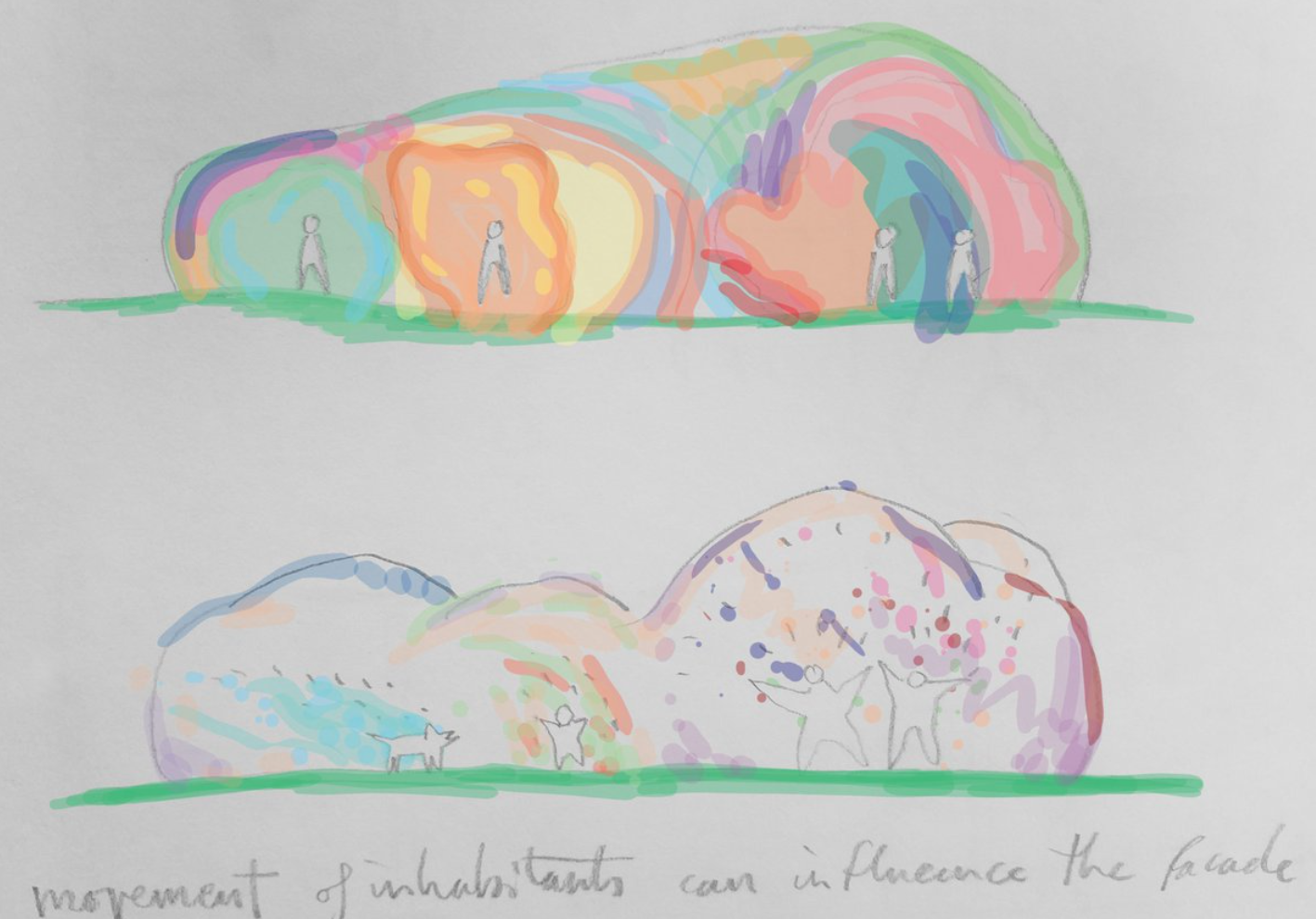

In terms of augmented reality, we can imagine another digital internet layer that interfaces with the city, with each building. So, what should buildings react to? They should manifest their inhabitants, their city and their environment.

Can you describe the process of creating a piece of digital architecture from inception to completion? How do you come up with the concepts and how long does this process take?

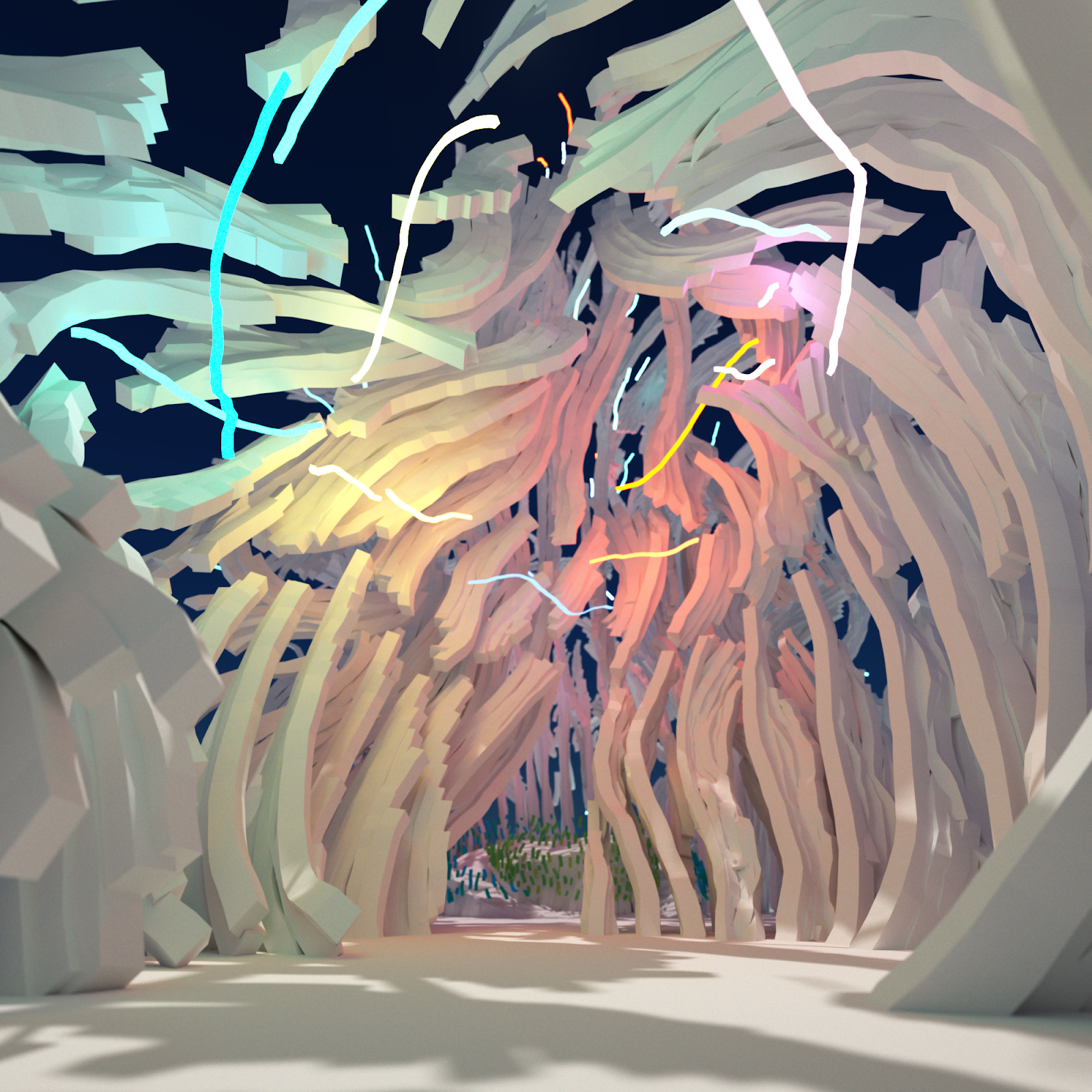

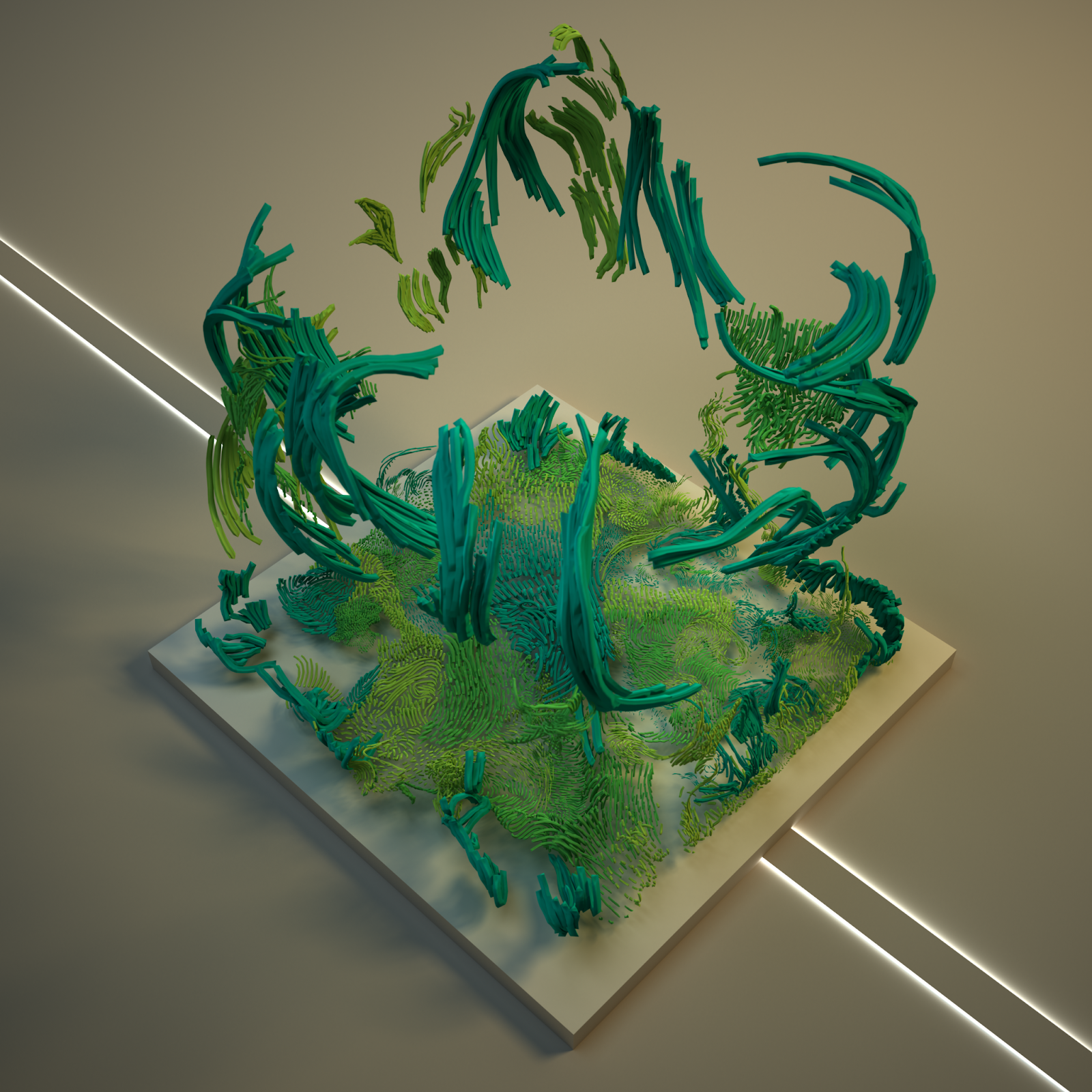

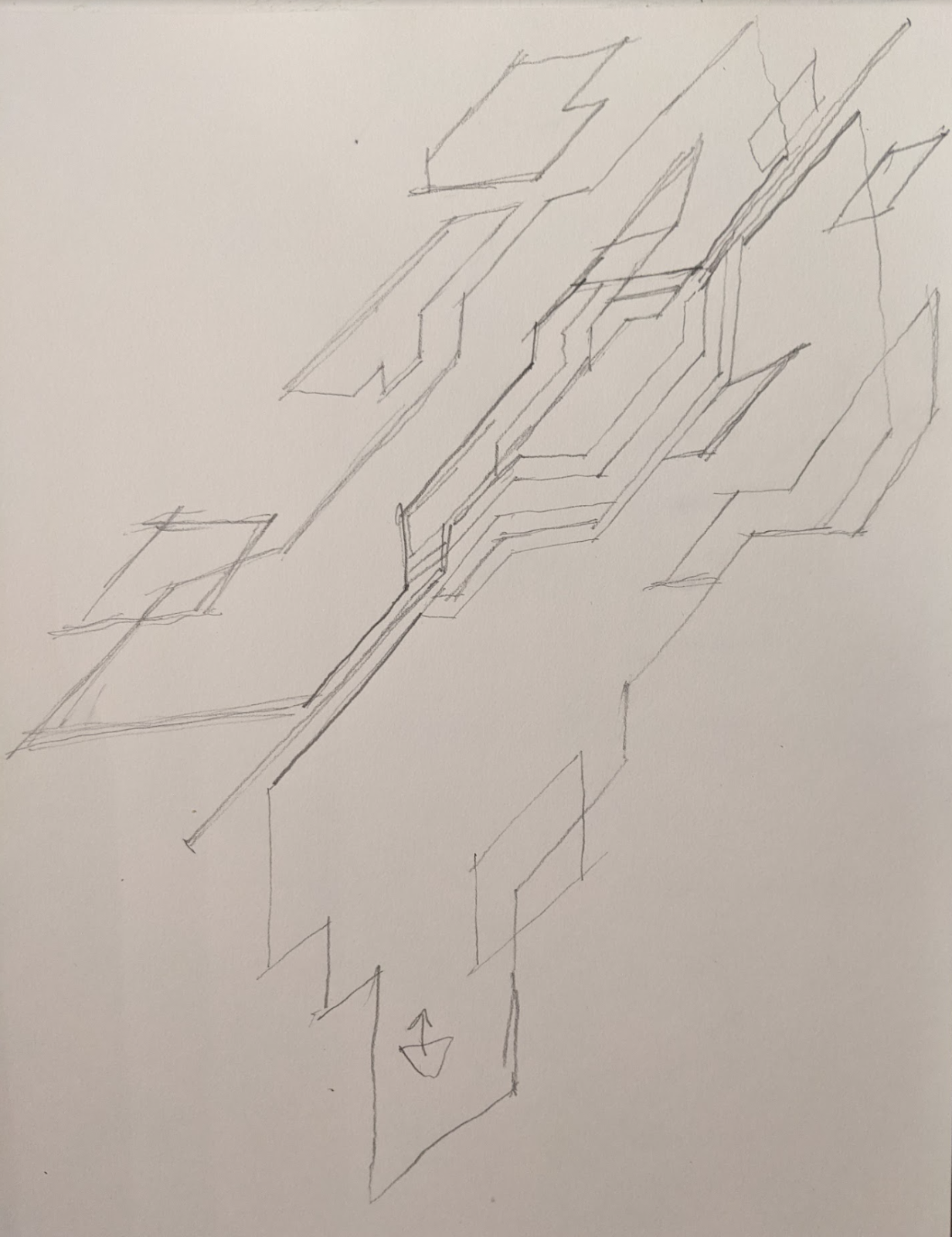

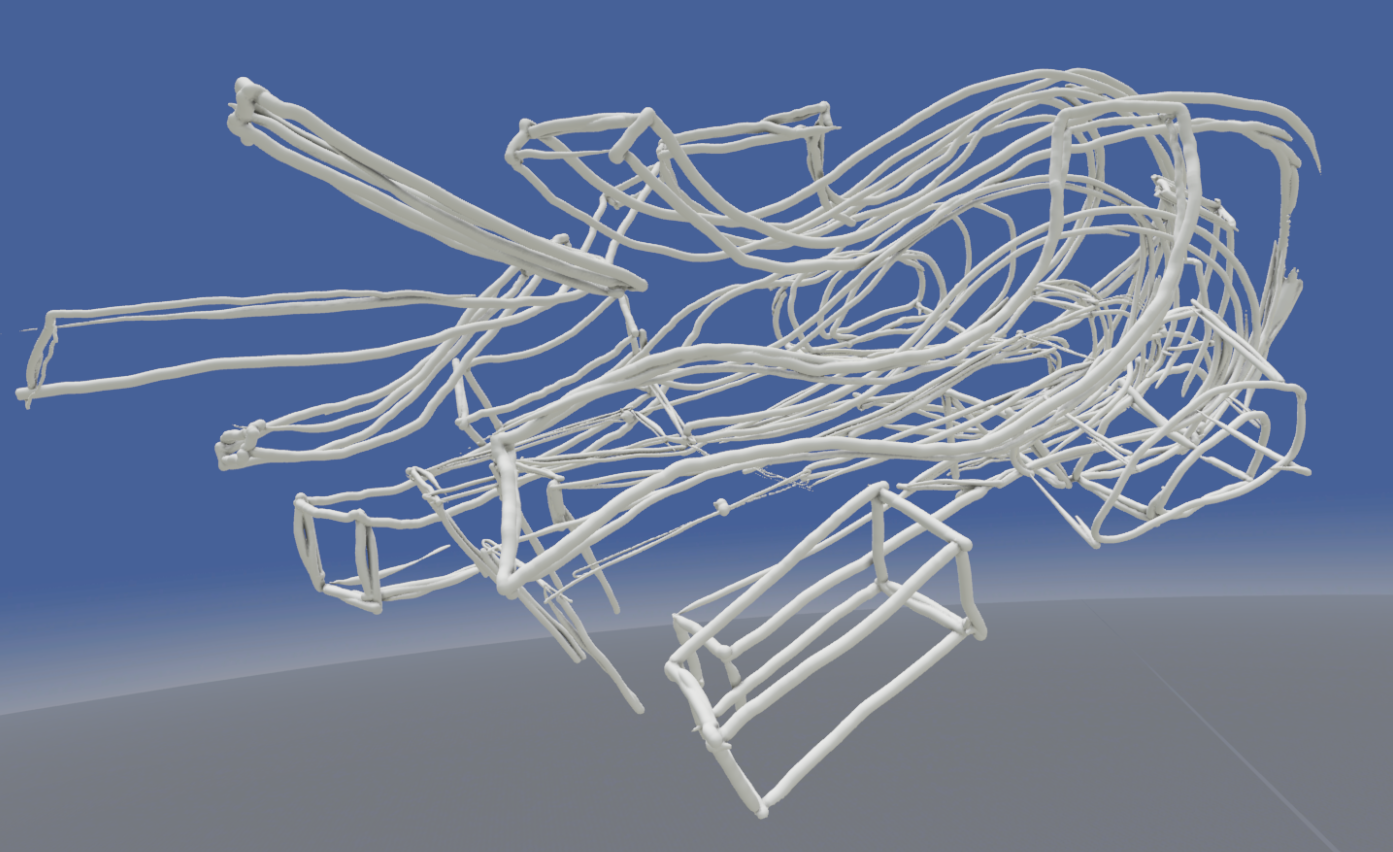

I try to incorporate VR sculpting by hand in all my design processes, even if it starts as a 2D sketch. There’s something intuitive about sculpting by hand in VR. Unlike using a screen and keyboard, you’re in the space as it’s being built so you have an immediate reaction to the world you’re creating. It’s a sacred conversation between the space and its creator. You react to how the space makes you react in a cyclical manner, a continual refinement.

Hand sculpting also reacts to the imperfections of your movements. It’s a way to bring the intimacy of craftsmanship into the digital world. Unlike the mechanical movements of a mouse and keyboard, the act of sculpting in VR is closer to leaving fragments, traces of dance in the air. The whole body is involved and you’re in it as it happens.

VR/AR architecture projects vary widely in terms of scope and process. For the SAT and MUTEK project, I was in the role of creative director for the first time, so I could delegate some of the tasks to the technical modeller.

The first space was more simple, so I made the first 3D model and gave further instructions through many sketches and conversations. The second space was more experimental, so I sculpted it all by hand and we tested it out as a team. The technical artist took care of transforming my handmade VR sculpture into a polished and streamlined shape.

With this project, I got to play a lot with experimental forms of lighting. While it was too wild for the client, the lighting was my favourite part of the process. You can visit these worlds, with more traditional lighting, at the following location:

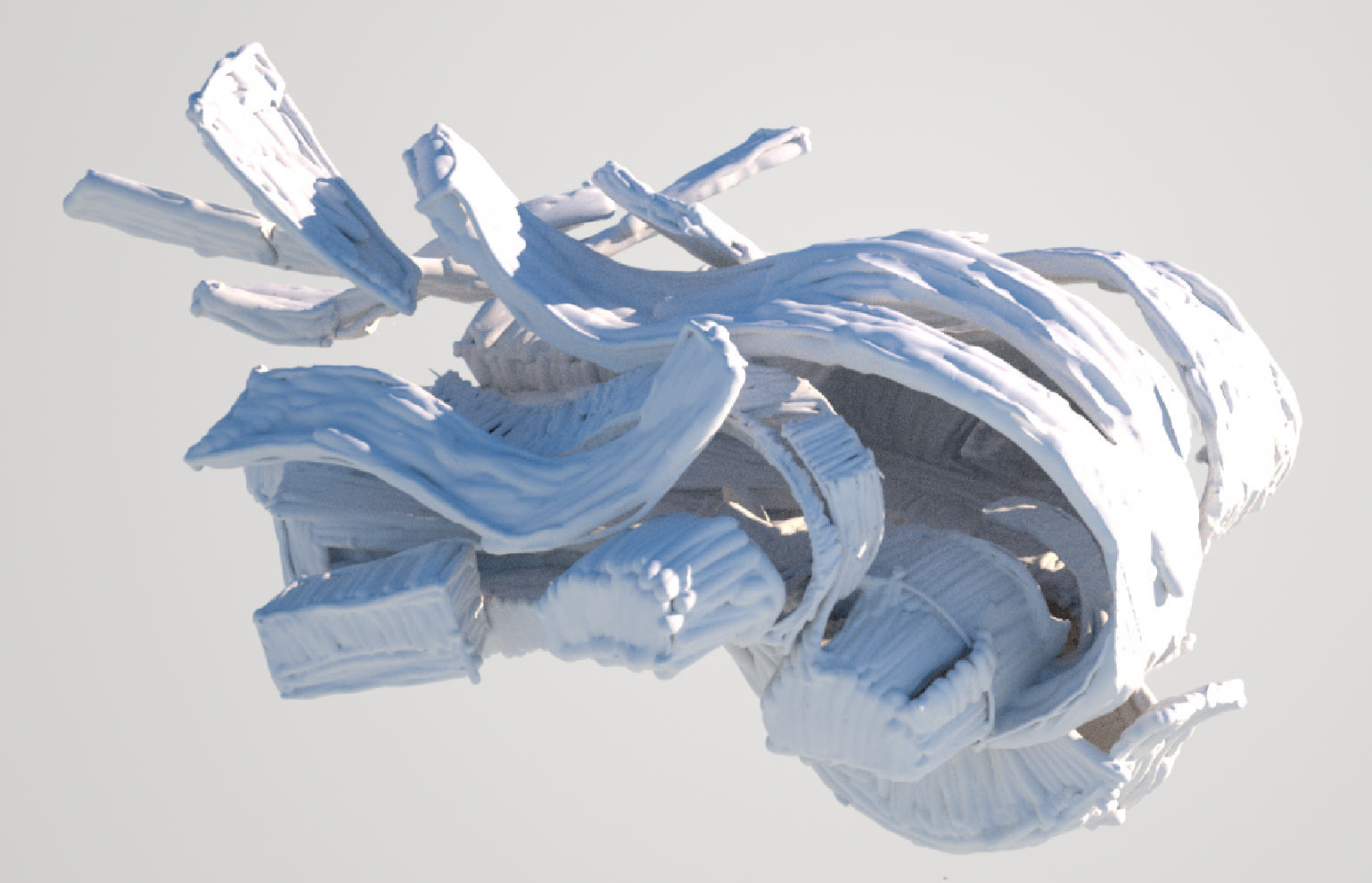

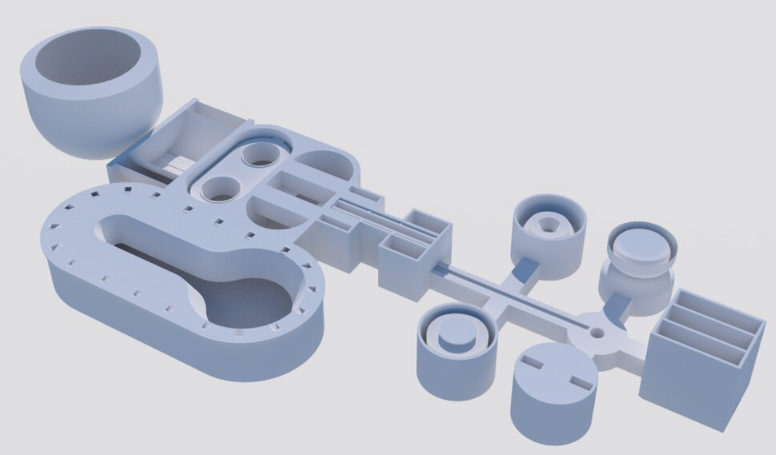

When it comes to my sculptural work, the pieces I’m doing nowadays take over a year to sculpt in VR. They are more complex and explore a kind of craftsmanship that is not possible in real life. My VR sculptures don’t usually start with a 2D sketch, I start directly in VR, create a macro shape in a few months and then spend much longer just adding details and refining the shapes.

There’s also a really boring technical process of decimating the geometry, unwrapping the UVs, baking their light and assembling the materials into a final package. This is a mind-numbing time-intensive process, so I have a lot of VR art that is created, but it’s not published because I don’t have time to through that process on every piece I make. I’d rather just be making art in my free time. Because of this, I’ve only published about 20% of what I’ve created in VR so far.

You recently collaborated with Buried Deep, the high fashion retailer and archive. How did that project differ from others you have done in the past? What interests you about the intersection of fashion, VR, and 3D design?

Actually, it’s quite similar to a project I did in 2018 with Pretend Play where we 3D scanned models and created an augmented reality show in my friend’s living rooms (LiL Pocket Gallery).

I kept going back to those memories and I’ve always been impressed by the energy of the fashion shows of Milan Tanedjikov at Lignes De Fuite. So I reached out to Milan about doing another one and he enthusiastically organized a shoot with Buried Deep.

We had an amazing day of shooting, I’ll be creating VR fashion from the resulting volumetric shoot.

Considering it’s cheap and relatively easy to create these types of experiences, I’m always surprised that we’ve not seen more of it in fashion, dance and theatre. I hope fashion schools will embrace the digital aspect of fashion in terms of VR, AR, metaverse and NFTs. Fashion and identity are a big part of the digital world and we need bright minds contributing to this new vector.

View this post on Instagram

What inspires your art?

Nature, architecture and internet culture.

Nature is still unmatched for general beauty and execution. There’s something sacred about the infinite details, variety and systems all integrated into each other. The movement of bugs, grasses, branches, trees, animals orchestrated into a living environment.

I’m inspired by the light architecture of James Turrell, the lyrical beauty of Carlo Scarpa’s spaces and the solar lighting architecture of Louis Kahn.

Then there’s contemporary and future society. We live in very internet-heavy times and this creates a new type of artistic and social culture. Then we look ahead and we can imagine how bringing spatiality into this will create yet another artistic and social culture. What this means for art and architecture, it’s all in front of us wanting to be designed and experienced. That’s my main drive, to walk on that path, to discover what lies ahead. To step into the unknown.

What have been the greatest challenges in working with VR?

Both diffusion and salability of VR art are extremely hard.

Galleries often don’t have the interest, knowledge, skill, staffing and/or equipment required to run a supervised VR experience. Because they don’t have the equipment, they’re also not very knowledgeable about what is possible to do in VR or AR or how it generally works.

Now, if the galleries are in this situation, just think of the collectors! It’s not very common to run into VR art connoisseurs who have all the equipment at home. If anything, it’s the museums who would be more suited to purchase a VR art piece to show VR art to the general public. There’s not much of an art market currently for VR art as the concept of buying a piece has not really been normalized.

For this, we need more artists to take on VR and AR art and to bring their passion to this new medium. There’s also a need for more schools, museums, galleries and libraries to support VR and AR art.

NFTs have helped to sell VR art a little bit, but it’s still a niche inside of a niche. While NFTs make it easier to sell 3D VR art, it does not help with getting more collectors to have VR headsets and collect VR experiences.

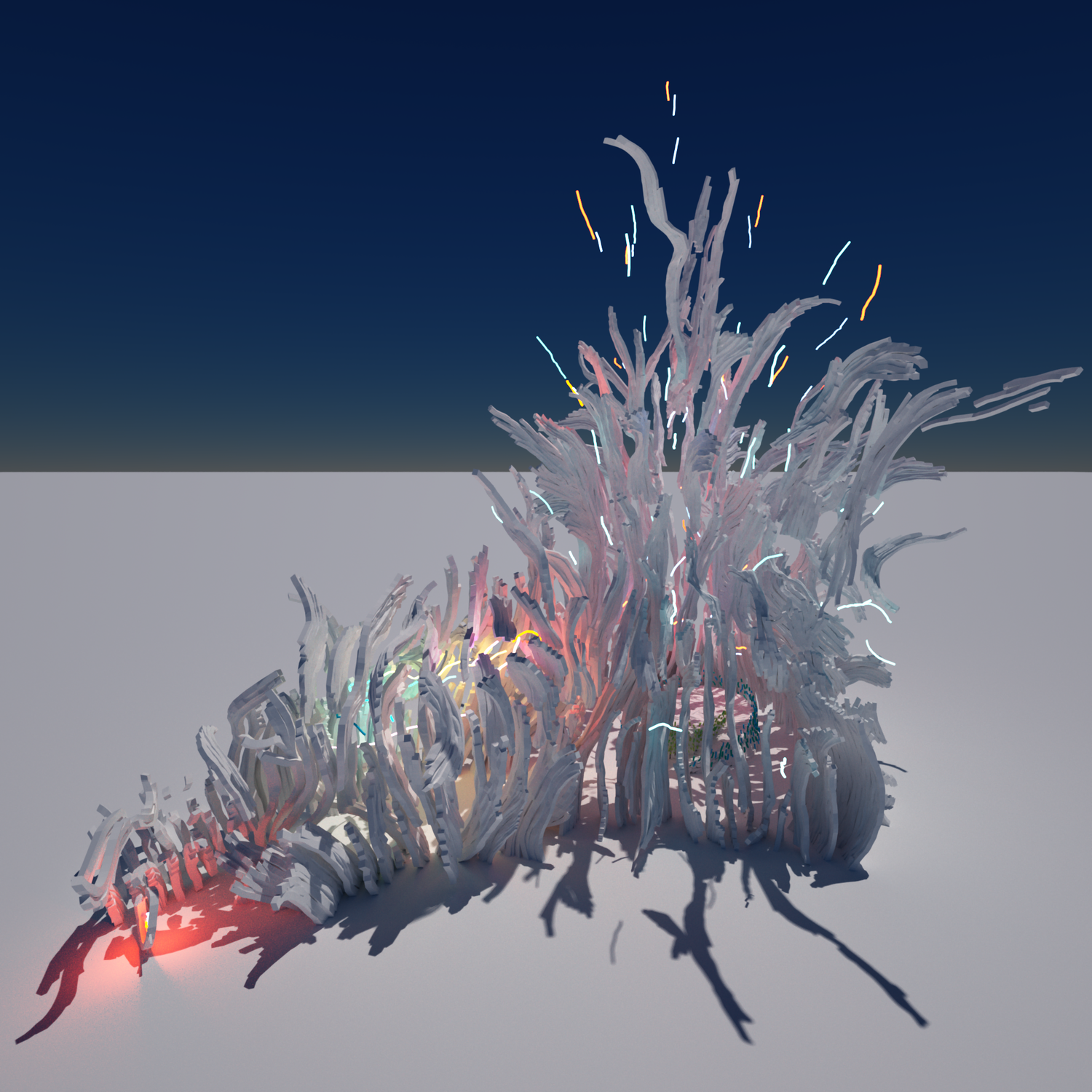

One of your most striking projects was Flame which is a handmade VR sculpture made in conjunction with a sound designer. What was the goal with this piece and what did you hope to communicate with this project?

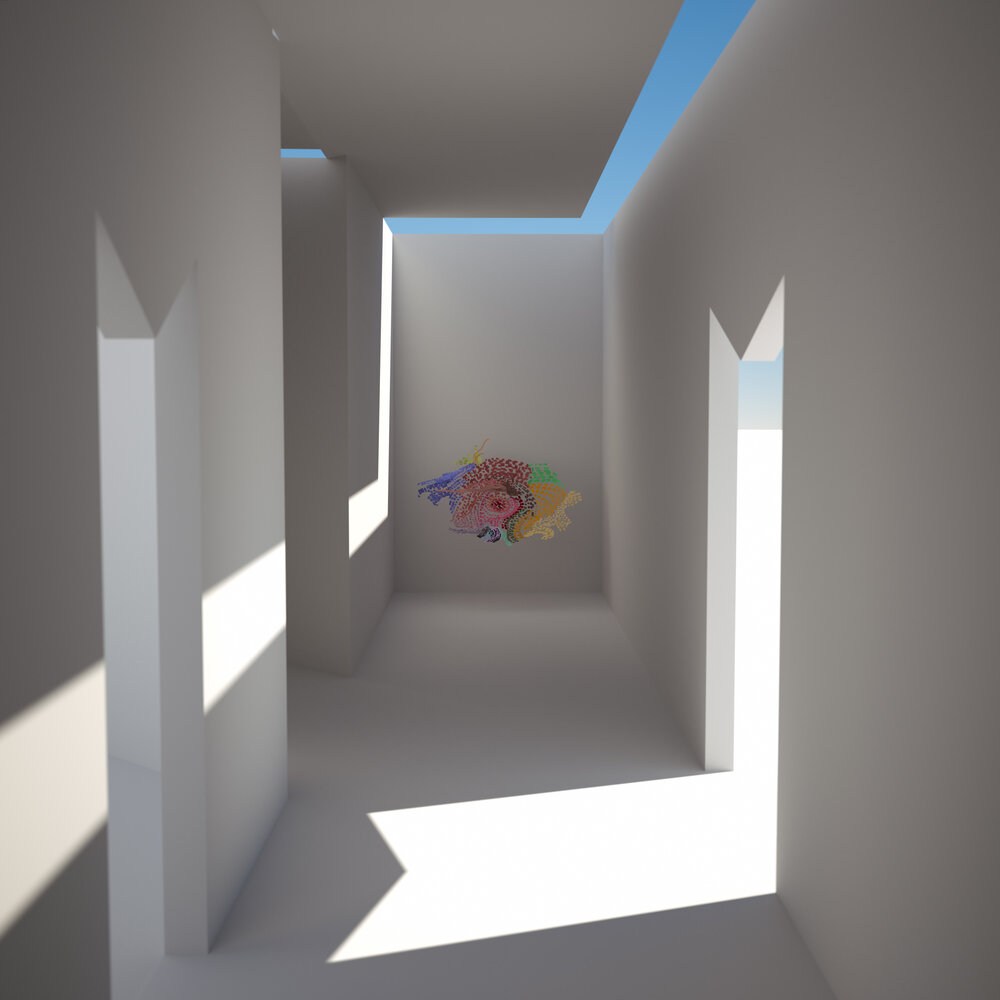

Flame is the second room from the ‘Light gallery” and it’s one of the rooms with the most diffuse light. The center oculus is floating and the sun rays pour around it to imbue the room with a soft photonic mist. For this room, I wanted to make an imposing sculpture reminiscent of a dancing flame. A sinuous, detailed assembly of floating foam. It’s really part of an exploration of spiritual spaces in VR, to see what kind of meditative worlds we can create.

In a way, I create a lot of spaces and art for myself. I love indirect solar light and complex sculptures, so I make environments that interest me, things I’d love to discover online or in VR. The sculpture cannot be accurately felt in 2D, so if you have a VR headset and a good desktop computer, I recommend visiting it at home.

Flame is also part of a bigger project called “Light Gallery”. This is a space, a digital gallery I’m creating. I’m slowly filling it in with one sculpture at a time, each sculpture takes 1-2 years to make. So I’m hoping to finish the entire gallery in the next 15-20 years into one single comprehensive space that has my architecture and my VR art. It will be interesting to see how the art has evolved over all this time.

Who are 5 other Montreal creatives you think we should know about?

Is there anything else you would like to add or feel is important for us to know?

I’d like you to think about what it would be like to visit Limunul in a digital space. What does it feel like to watch an interview in a 3D setting, to read a spatial article, are you walking through the story? Stepping across a fashion collection, a mix between magazines, museums and runways.

For the fashion designers, think about what parts of a garment you could design in VR or AR. When you create a look, think about what AR accessories you’d add to it, what part of the garment is digital and what part is physical. I’d love to see schools integrate VR and AR fashion into their curriculum a lot more. Go bother your teachers, make them ask for grants for the equipment, the future is not going to build itself, we have to actively work on it and make sure it represents our dreams and aspirations. Don’t let others design your future, find a way to participate in this conversation now instead of following the leaders later.

If you’re part of a school, gallery or museum and you’d like to get into VR, feel free to contact me and I can give you some advice on how to get there.

If you’re an artist thinking of jumping in VR, I recently made a list of VR experiences that can serve as inspiration for new VR artists trying to shift their way of thinking.

https://twitter.com/Sam__AB/status/1502696515512541184

Kate is an Editorial Intern at liminul.

She is a writer, photographer, and graphic designer based in Montreal. Kate is currently in her final year of her B.A. at McGill University where she is double majoring in history and art history.