In her latest project, the decade-spanning photo series titled Broken Mirror, New York-based visual artist Samantha Sutcliffe peers through her camera into the black mirror of American life. What looks back at the viewer is a haunting reflection of a reality alienated from itself in the age of the internet, late-stage capitalism, and constant surveillance. The series, which is shot in black and white, stitches itself together with transcripts and home videos collected through Sutcliffe’s novel practice of meeting up with strangers through Craigslist across the United States’ West and East coasts. Together, the photos coalesce into the distorted shape of a culture so possessed by its need for mass media consumption that the only territory left for its capitalist id to cultivate is the human self, the photographic subject.

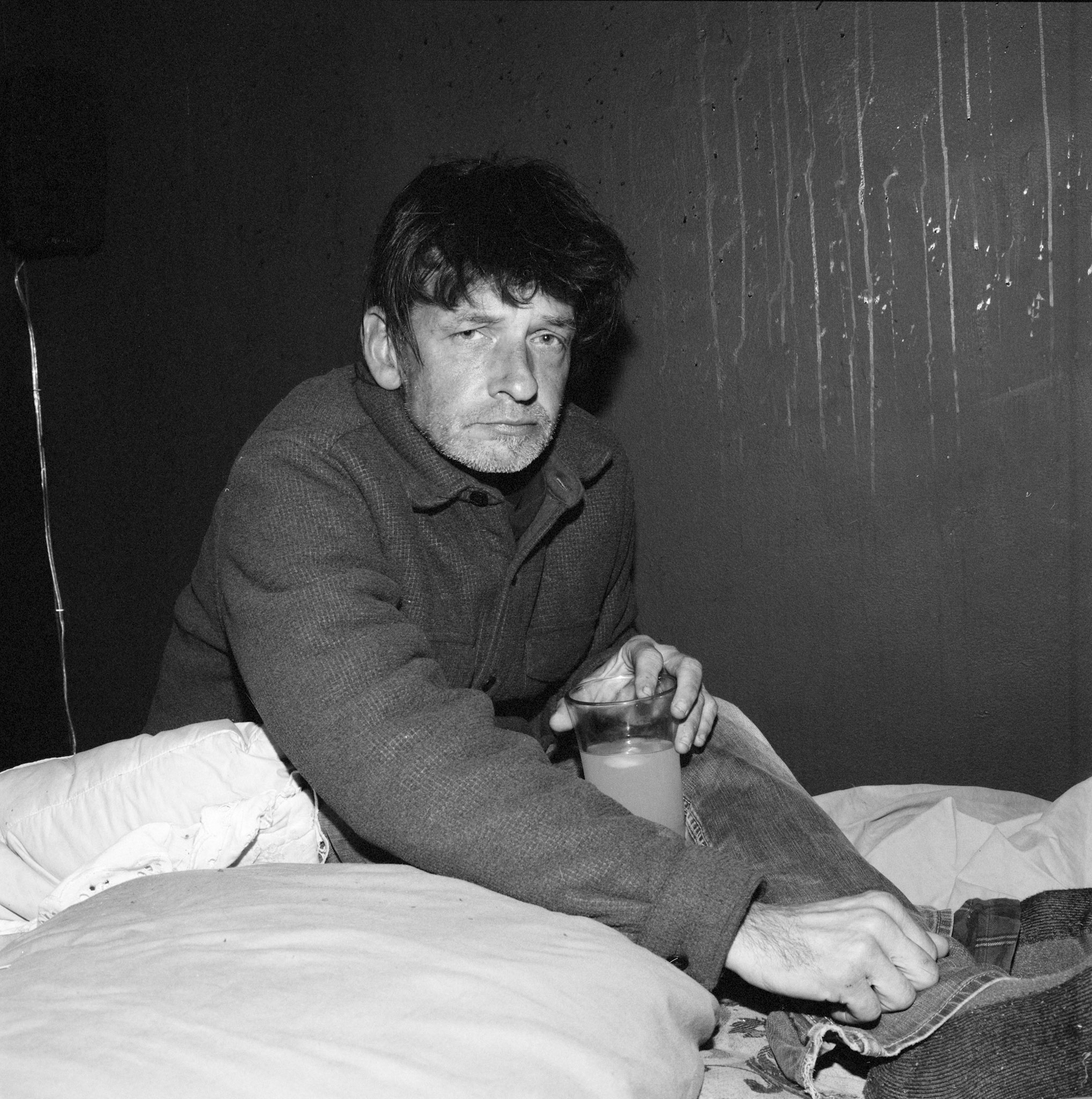

In an interview with Liminul, Sutcliffe, knowledgeable of the inherently transactional premise of a platform like Craigslist, explained that while most of our online interactions originate in transactions of some kind, her interactions with her subjects “felt like a very equal exchange.” Originating as far back as 2013, the Craigslist meetings offered both Sutcliffe and her subjects something increasingly rare in the hyper-surveilled, hyper-curated present of the digital age: the space to be seen without being marketed to or having to market oneself through the inherently performative prism of virtual communication. “I gave them a place to act out who they wanted to be and how they wanted to be seen,” she said. “I don’t control any aspect of it.”

Broken Mirror, therefore, simply observes its subjects expressing themselves in their own space. In this, Sutcliffe’s photographs perform what French philosopher Julia Kristeva, from Powers of Horror—her famous essay on abjection—, might call an abjection of the social and cultural image. In all its glitzy gray melancholia, Sutcliffe’s art confronts us with the things, people, and moods we tend to expel to maintain the illusion of order.

The photographer turns her camera to formerly occupied commercial-public spaces and human subjects on the transgressive fringe of society. Though unlikely to participate in such spaces of general commercial enjoyment themselves, Sutcliffe’s subjects—subaltern, suburban personas and rebels, social media influencers, self-titled transgressors—share the same affective void that haunts these temples of industrial civilization.

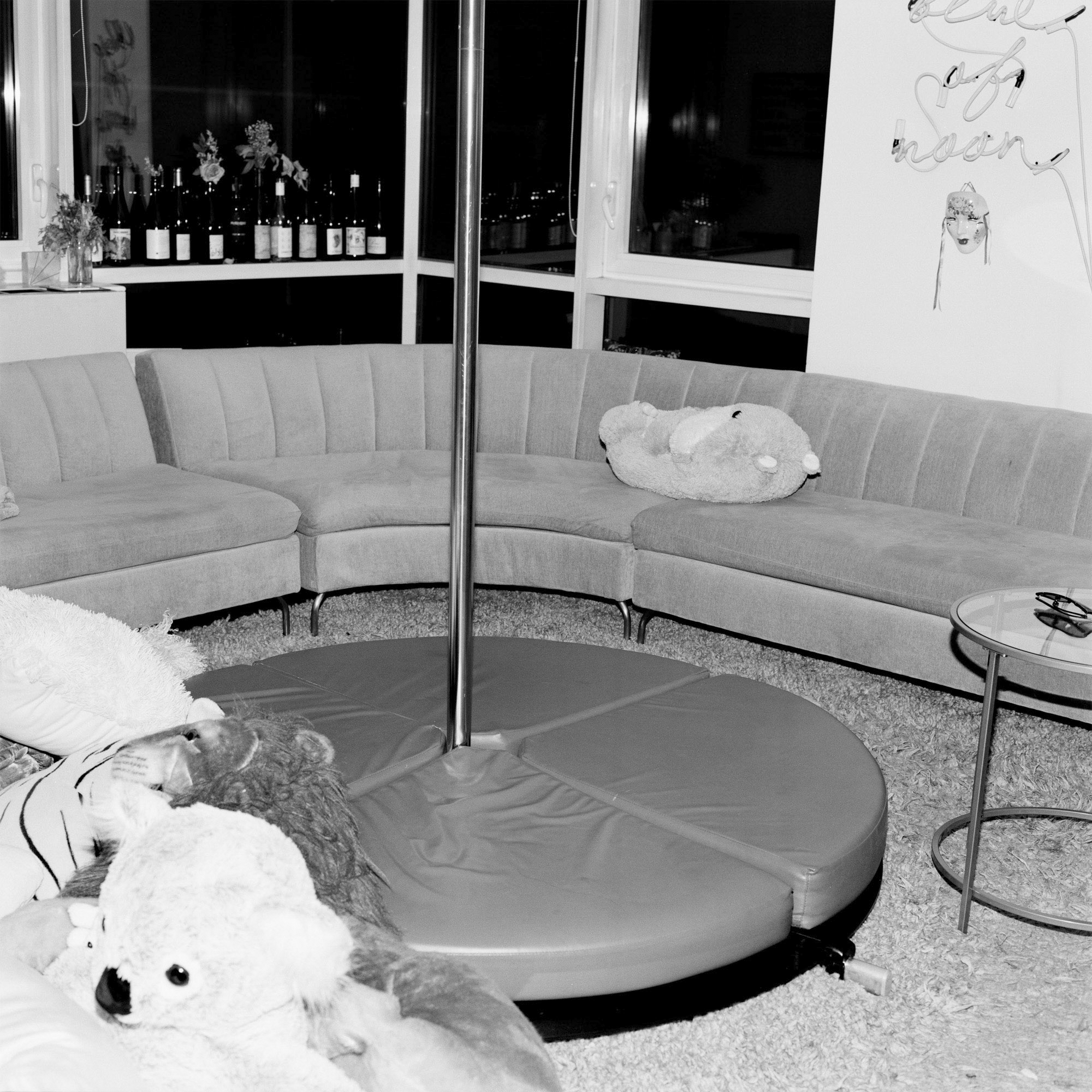

There is an abandoned strip mall long after working hours. A visibly aged person in a dark netted wig cap, presumably a drag queen, looks wryly into the camera as they fasten a corset around their torso. An empty movie theater sits shrouded in darkness. A topless, tattooed, frizzy-haired woman looks upwards, striking a comically or earnestly sloppy pose. Behind her, artistic portraits of clowns hang like warm family portraits. An unoccupied private lounge is empty, peopled only by carelessly strewn stuffed animals and a stripper-less stripper pole.

Here, the abject, which Kristeva describes as any disturbance to socially sanctioned “identity, system, order,” and “borders, positions, rules,” first manifests as a kind of queerness; a broad resistance to the general, flat norms of identity and expression. From this, Broken Mirror—which works as a play on the techno-satire Black Mirror—presents its thesis as a varied documentation of the profound emptiness festering inside America’s paradoxically over-saturated sociopolitical and technological landscape, and a record of the opportunities for altered expression and alternative experience that this institutional tragedy simultaneously creates.

On one hand, the sheer mass of empty space in the series speaks to the recession of public life from the increased technology-led personalization of entertainment and interaction. On the other hand, this desolation also speaks to a silent swathe of people alienated from the hetero-normative commercial public, who find freedom to be themselves in, ironically, engaging performatively in front of a camera, screen, and imagined audience from the intimacy of personal space.

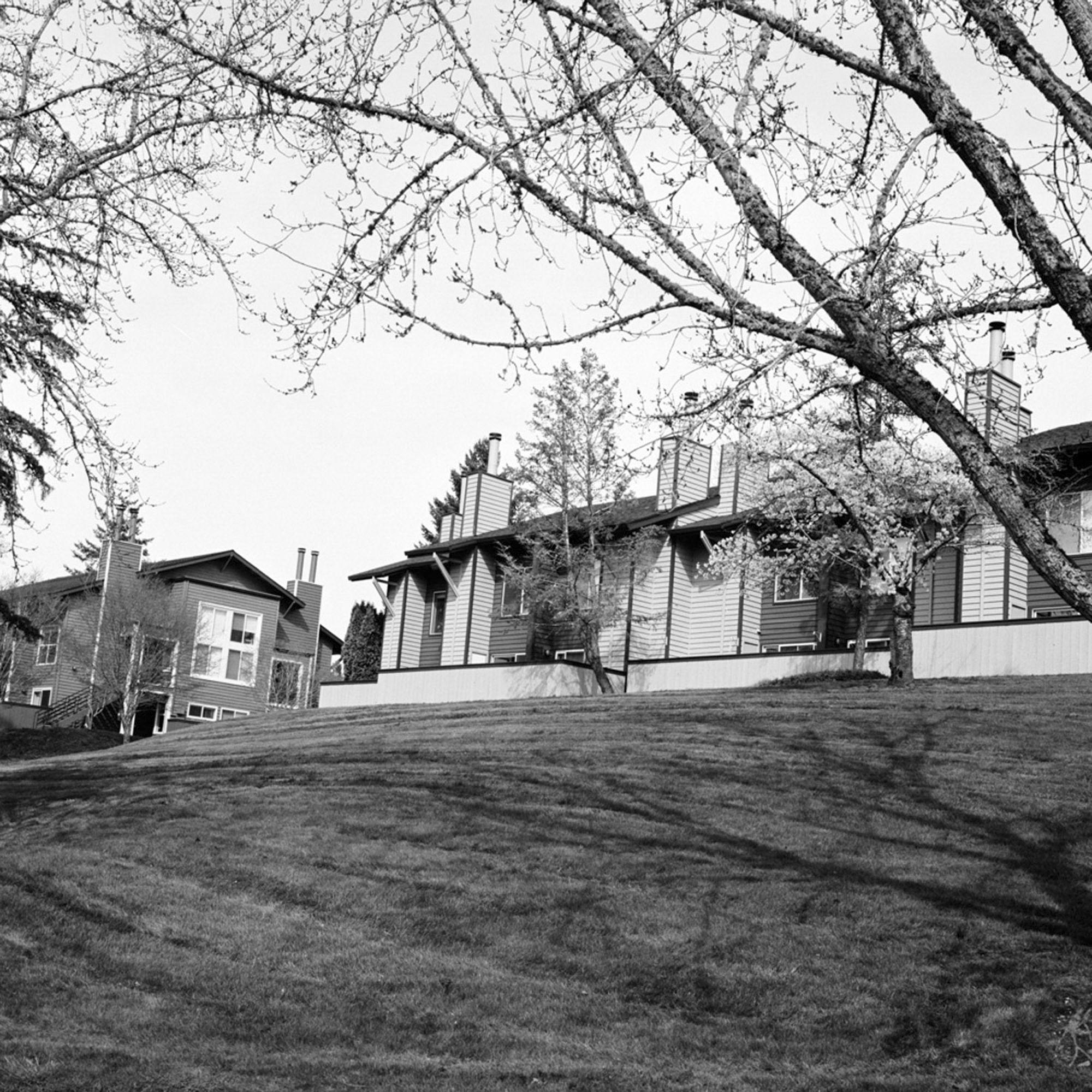

Against this backdrop, all the photographs in Broken Mirror teem with ghosts. From teenage outcasts to overexposed influencers and strange transgressors, everyone resonates with or refracts the same hollowness of half-empty rooms, glutted closets, and the eerily dull spectacle of obsolete suburbia.

Where specters of some kind do not emerge from the photograph, as in a picture of a long, dark-haired woman whose face glows from the fluorescent white flash of the camera, the ghosts project through an absence that draws attention to the unnatural lack of a human subject. Of this, a picture of a sex doll, easily passable for one of Khloe Kardashian’s aggressively face-tuned Instagram selfies, demands attention. The image conjures a disturbing sense of not just the doll’s own lack of a conscious mind, but also the nature of her relationship to any human, which, in its full extent, goes no further than her utilitarian function as a passive sex object.

The doll, which bears the eerie front-facing glow of a saint’s statue, embodies the woman subject as optimized by a chronically online culture. In such moments in the series, Sutcliffe delivers critique with devastating wit. As a document of America’s late-capitalism and internet age, the picture recalls historian Susan G. Cole’s notion that the best way to instill social values effectively is by eroticizing them. Inside a Donald Trump and Elon Musk era, where the male-oriented dominance politics project sexual ownership over simple, passive women, feminism is also textured by a mass beauty market and the virtuous internet-spread ethics of ‘clean girls’ and ‘trad wives.’ Sutcliffe’s sex doll, therefore, serves as a symbol of the active evolution of gendered expectations of womanhood and general subjectivity in the internet age. Before a camera and the imperative to become a spectacle in exchange for social currency, the subject must become a self-generating magic trick to be looked at, a thing to be possessed and enforced upon, in which anything can enter and accumulate, but nothing comes out.

What emerges from visions like these is a deeply Gothic portrait—Gothic not merely in its stylistic trappings of darkness and decay, but in the historical sense, as an exploration of fear, confinement and the uncanny materialized in the gradual breakdown of rational order. Against the series’s cultural and sociopolitical backdrop, the Gothic functions as a representation of the affective state of life under a system of accelerated capitalism.

“I feel like everyone is living in a haunted version of their life, especially on the internet,” Sutcliffe said, “It’s all like a permanent record. You’re haunted by your surroundings.” Out of this, she originates the emergence of our culture of online communication and social performance as a fracturing of identity—first virtual, and then actual—where we function by creating new identities for ourselves “as a way to create some sort of safety or security” against the voyeuristic glare of the internet and electronic communication devices as machinery for systemic surveillance and manipulation.

Each image in Broken Mirror floats in that spectral tension between subject and object, intimacy and distance, performance and truth. Particularly, this tension reaches a screeching pitch, in the aforementioned picture of the sex doll—perfect, petite, poised—in contrast with the woman—plus-sized, physically androgynous, who stands topless in a messy room decorated by signs that read “JUST DONT” and “HALLELUJAH BLOODY JESUS!” Rather than operate within a binary of subject versus object to make an explicit moral statement about our cultural moment, Sutcliffe, by simply documenting her subjects as they are, leaves us to ponder there capacity to exist as both; a predicament French philosopher Jacques Lacan coined as “the subject who is supposed to know,” who is neither complete subject nor total object, but rather an ‘enforced subject.’

Between the sex doll and the woman in her messy room, we glimpse two iterations of the Lacanian imaginary of a subject upon whom the mechanical state of objectivity is imposed and wholly accepted. Taking the doll as the evolved, ideal feminine of the internet, the woman with her clown portraits becomes the visual rebellion against that standard. Despite their seeming visual differences, these enforced subjects share the same black and white sheen of a persona fractured from a ‘real’ personality that exists in private, away from even Sutcliffe’s sharp eye. Inside Sutcliffe’s gaze as a kinder, less judgmental approximation of the virtual gaze, we never forget that these disparate personas are still packaging themselves to an imagined audience, maintaining their capacity for monetization in the medium of art which can be copied, printed and sold, and are operating through expressions which are, on some level, still mechanically inscribed by the spectator.

Against the series as a whole, we cannot trust that personality isn’t simply a mask for persona. What’s unique about this is that Sutcliffe makes us feel that this is okay. Somehow, in our inextricability from social and technological machinery, we gain the capacity to be “fluid and radical and resistant,” as cultural critic Jia Tolentino describes in her canonical 2019 essay “Always be Optimizing.” Subjects, in all their weirdness and novelty, remain alive beneath a cultural epidemic of branding and performance. We cannot put away the knowledge of an omniscient, omnipresent, imagined audience. Even on the margins of society, the pressure to reaffirm oneself as an interesting subject, a worthy object, and a self-generating spectacle persists simply from the presence of the camera. Therefore, why not operate within this very artifice as armor against the immensity and brutality of the machine itself? Why risk exposing your truest self to a system that wishes to degrade that self in the first place? Simply keep pretending, fracturing, and re-inventing yourself, and—genuinely—everything will be okay.

Sutcliffe’s lens refuses to expect anything from its subjects. While they nonetheless become performative before the camera, the performances feel as genuine in their expression as they are necessary as protection against the constant voyeurism of the social surveillance system they work within. The subject is not exactly lost, but they are never quite present to begin with. We see this in the vacant gazes the series presents; in the haunted posture of a woman in a string bikini, as in the leftover traces of strangers who once lived or posed in these empty rooms.

As the United States—and certainly North America at large—slides deeper into self-surveillance, cultural melancholia, and alienation, Sutcliffe’s work reminds us what is still at stake. Sigmund Freud warned that the ego—that part of the mind that mediates between unconscious desires, moral constraints, and reality—can become diseased on its own account. Sutcliffe’s camera finds her country’s ego right where its sickness is taking hold.

Jonathan Divine Angubua is currently finishing his undergraduate studies at the University of Toronto. He enjoys any interesting art and is always looking for great book recommendations. As a writer and lover of fashion, he is most inspired by strangeness and beauty.

Jonathan Divine Angubua is currently finishing his undergraduate studies at the University of Toronto. He enjoys any interesting art and is always looking for great book recommendations. As a writer and lover of fashion, he is most inspired by strangeness and beauty.