Film has a tendency to compress time. In all of the frantic and jagged cuts and perspectives of cinema, its multiplicities suggest and allow for the illusion of a time-elapsed in much greater length than the average running time of a film. But subtract these multiple perspectives from the medium and one is left with an uncanny experience of the banality of cinema and the passage of time. Such is the case in Wavelength.

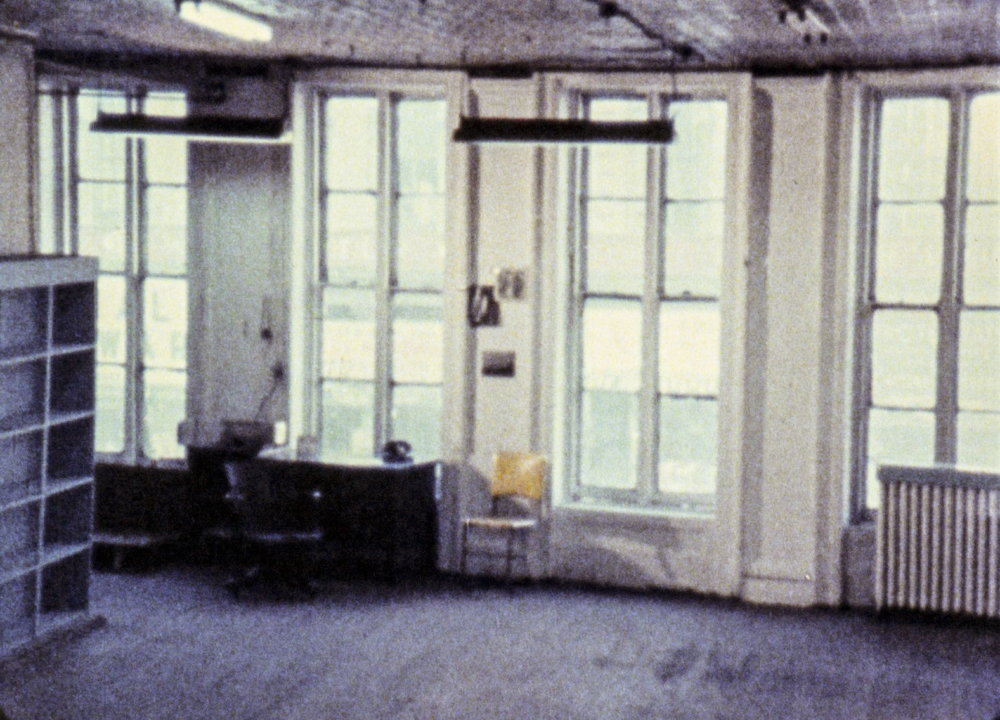

Wavelength, the much-lauded experiment film by Toronto-born filmmaker Michael Snow takes this experience and heightens it to an unnerving extreme. The 45-minute film, released in 1967 by the OCAD graduate, is comprised of but one perspective, a consistent zoom from a fixed camera position facing a wall with four tall sash windows. Over the course of the film, the angle narrows until the frame is filled with a black and white photograph of waves pinned up between two windows.

The four events that take place before the camera in Wavelength are largely irrelevant in the film; characters come and go, installing shelving units and playing the radio, a woman makes a phone call and a man collapses on the floor and dies. The narrative of Wavelength serves only as an inversion of the spectator’s cinematic expectations. Here, the characters are largely invisible and ignored and the presence of the camera in its arduous zoom across the loft takes the form of a protagonist of sorts. Its journey, ruled and intensified by the sound of a rising sine wave, is a compelling subversion of cinematic convention.

“I wanted to make a summation of my nervous system, religious inklings, and aesthetic ideas.” Snow wrote of the film upon its release. “I was thinking of, planning for a time monument in which the beauty and sadness of equivalence would be celebrated, thinking of trying to make a definitive statement of pure Film space and time, a balancing of “illusion” and “fact,” all about seeing.” The film was recognized immediately as having resolved in a perfectly integrated form, the emerging desire among experimental filmmakers for simplicity of cinematic expression. In doing so Michael Snow became a part of a new wave of Structuralist and Fluxus filmmakers, who, in their attempts to critique and decommodify cinema, demanded sparseness not only within a given frame but across multiple frames. Through its stretching of cinematic material, Wavelength thwarts the narrative that one can often read into photos and films, and disorients the viewer with regard to their expected signifiers and visual resolutions.

In the early 2000s, as Snow became interested in digital media, he created WVLNT (or Wavelength for Those Who Don’t Have the Time). His new iteration of the film, cut into three equal lengths and superimposed onto each other further destabilized the expected linear narrative qualities of cinema. Wavelength’s much-pondered sequence of events in WVLNT are even further compressed, this time subverting the tendency and urge to express narrative and multiplicity of perspective by alluding to the cinematic ‘cut’, but never fulfilling it.

The film, and its subsequent re-makes and re-works have become a cornerstone of post-modern cinema and an iconic Canadian contribution to the canon of structuralist filmmaking.

Cody is the Editor in Chief and senior contributor at liminul.

He is a photography aficionado, fashion enthusiast, avid Lana Del Rey fan, and lover of all things aesthetically pleasing.