From intricate tailoring at Yohji Yamamoto, to broad silhouettes at Dries Van Noten, and bold shoulders at Saint Laurent, it is clear that elevated workwear is making its way back into our wardrobes.

A peek at Spring 2023 Ready-to-Wear collections has shown us that traditionally professional attire can still have a glam factor.

With a persisting fight for women’s sexual and reproductive freedoms in the past few years, it comes as no surprise that these trends are reemerging on the runways; the New Woman is making a comeback.

In the 1920s, at the height of the Weimar era, the term Neue Frau came into common usage in German culture, and the associated stereotype came to be a prominent symbol of modernity. The expression, which means New Woman, first appeared in novels such as Henry James’ Daisy Miller and The Portrait of a Lady. These books popularized an image that came to be known for its characterization of a new modern lifestyle, wherein women smoked in public, sought the right to vote, and were considered of “loose” sexual morals.

When the term later emerged in German culture, after the first World War, it became a prominent symbol of the changing times and associated emerging fashions came to be a central component of women’s experience of modernity. Marked by depression and the rise of the Nazi Party, the economic and political turbulence of the Weimar Republic led to an increasing sense of autonomy for women, as they joined the workforce and took on more active roles in society. These fast-paced changes in German society led to the development of Berlin’s reputation for decadence and licentiousness.

The changing fashion landscape in Weimar Berlin and Germany’s socio-economic context following the First World War allowed for the changing of gender roles in the Weimar Republic.

Middle-aged women, mostly of the middle class, began to demonstrate new lifestyles and exercise new cultural practices, in what were primarily male-dominated fields, such as journalism, photography, and design

The increase in mass-produced goods and the emergence of fashion shows made fashion much more accessible to the middle class and, as a result, led to the emergence of fashion journalism. Magazines such as Die Dame—which, in fact, still exists today—were devoted entirely to gratifying the interests of the New Woman. Consisting of illustrations, photography, and essays, these publications intended to celebrate newfound independence; a product of women’s autonomy and participation in society, as a result of the war.

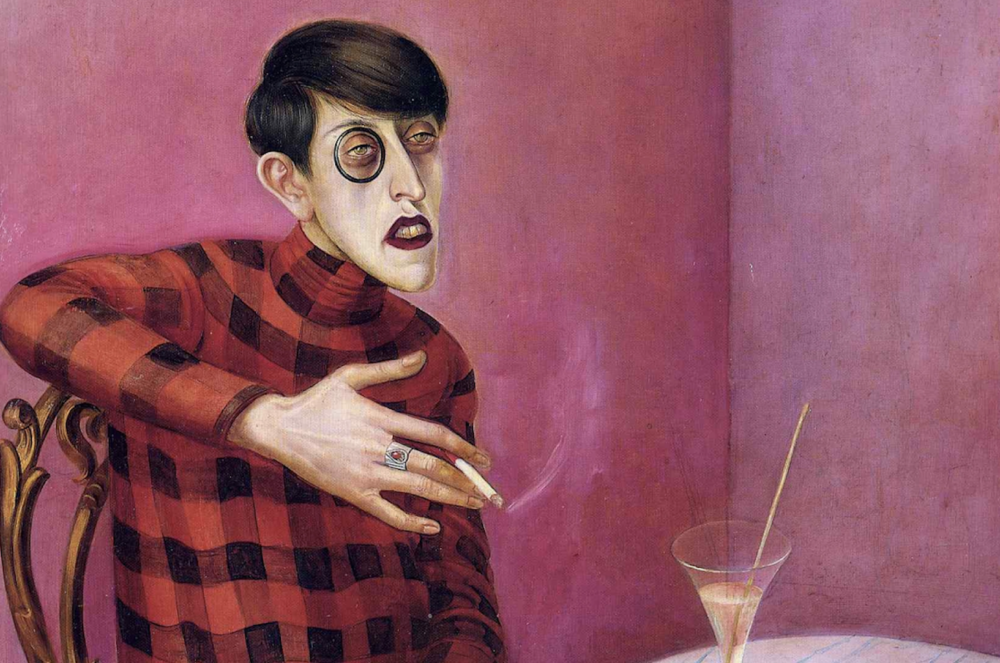

As these magazines gained popularity so did the role of fashion journalists within society. Otto Dix’s Portrait of the Journalist Sylvia von Harden depicts the significance of the female journalist during this era. The portrait, which consists primarily of red and pink hues, has an otherwise frigid quality; the composition is rather scarce and a blue undertone contributes to its barren appearance.

The viewer’s eye is immediately drawn to Sylvia von Harden’s figure. In one hand, she holds a cigarette between her bony fingers. Her jaunt face, which is rather garish, alongside her crooked smile and monocle, contributes to her mannish appearance. Her legs are crossed and she guards her body with her other arm, as though to protect herself from the viewer, ultimately giving us the sense that we are not invited into the frame.

Sylvia von Harden’s monocle and rolled stocking are clear indicators of her sexual orientation and contribute to the notion of the “masculine lesbian personality.” These desires to have the same freedoms as men are commonly illustrated in Dix’s portraits of women, wherein the sitters engage in activities that were otherwise “reserved” for men, including smoking and acting or dressing more “masculine”.

Here, von Harden is seen smoking, and drinking, and is recognized as a journalist. The notion of embracing one’s corporeality – as opposed to existing to be perceived — is exemplified in Dix’s portrait of von Harden, wherein she is the main focus of the work. Sylvia von Harden embraces masculine traits all while typifying the New Woman; sexually liberated, career-oriented, cigar-smoking, and androgynous. It, therefore, becomes obvious that Dix’s representation of the Neue Frau and depiction of von Harden’s sexual orientation contributed to the establishment of visual codes between gender and fashion.

In addition to the emergence of fashion as a spectacle and fashion journalism, German audiences were entertained by burlesque, opera, and cinema. These forms of entertainment became increasingly popularized and provided new approaches to promoting a new way of life.

A German dancer, actress, and writer, Anita Berber became known for her nude performances, androgynous look, and lesbian relationships. She also came to be somewhat of a fashion icon, as a result of her modelling for magazines such as Die Dame.

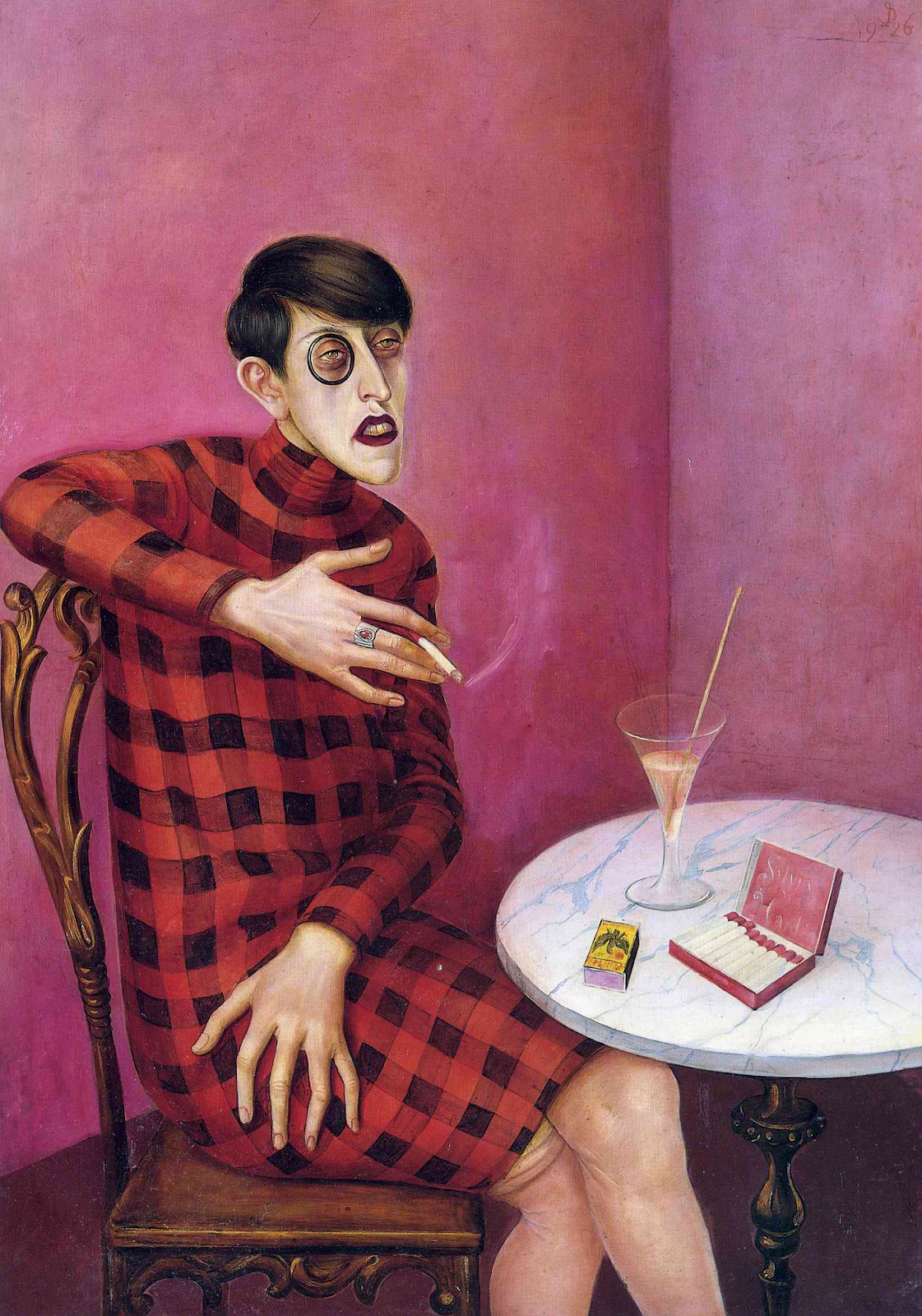

Considering Berber’s work as a nude performer and dancer, it is interesting that Dix has chosen to portray her fully clothed in his work Portrait of the Dancer Anita Berber. The painting is composed solely of vibrant reds; from Berber’s hair and dress to the background against which she stands.

The monochromatic composition contrasts starkly with her green reptilian eyes and pale skin. Orange shadows frame her figure, as though she stands in front of fire, giving the work a hellish appearance. Dix has enhanced these qualities—reptilian eyes, claw-like hands, bright orange fire—which are demonic, by making them contrast with the otherwise monochromatic tones.

Berber, who danced completely nude, challenged these laws which, at the time, may have been viewed as an indication of her sexual freedom. That being said, despite being renowned for her nudity and eroticism in her performances, the fact that Dix chose to portray Berber fully clothed suggests a deeper understanding of her artistic contributions to performance art as a career.

With theatre and entertainment becoming so popular, the distinction between fashion and performing arts began to disappear.

As clothing and fashion became increasingly available to the middle-class, film emerged as a medium to disseminate fashionable images to large audiences as a means of capitalizing off of their desires. In fact, the same can be said for sex work at the time. As sex work emerged as a career in German culture, it became increasingly difficult to differentiate the newly surfaced Neue Frau from sex workers.

In her book Berlin Coquette: Prostitution and the New German Woman, Jill Suzanne Smith studies sexuality during the Weimar Republic and forms connections between prostitutes and the New Woman. As prostitution emerged in the Weimar era, it led to ongoing discourses surrounding extramarital sexuality and women’s financial autonomy. Smith states: “An institution that promotes sexual relations without emotional attachment, prostitution detaches love from sex.” Similarly, Berber aimed to detach the notions of sexuality and nudity from one another, via her performances; she did not use her nudity to attract viewers, but rather as a means of expressing herself freely via her career. Thus, we can see a distinct emergence of the use of dress and fashion for self-expression.

Faced with economic and political challenges, it is clear that there are some parallels between the changing landscape in the Weimar era and our current situation today. By examining art and fashion from the past, it becomes evident that fashion serves as a greater reaction to that which we are experiencing at any given moment.

While at the time of the Weimar era, fashion and art served as a means of establishing a sense of sexual identity, we might be inclined to say that today’s fashions are aiming to reinforce women’s sexual identity. From kink and fetish to nostalgia, everything we wear is a deliberate response to change or that which we would like to change.

Lorenza is a freelance writer, copywriter, and content strategist studying Journalism and Human Environment at Concordia University.

Her interests include visual culture, subcultures, and sustainable fashion.