Growing up in a lower-class, single-parent household throughout the 2000s, thrift stores were my family’s go-to shop for anything short of food and toiletries. Throughout my childhood, Aeropostale and Hollister branded shirts and hoodies were at their peak popularity, and needless to say, my mix and match vintage outfits weren’t up to par with many of my classmates. Though I wouldn’t say that I was “bullied” for my clothes, it would be a lie to say that I was never singled out for my wardrobe. Besides, I lived with my grandparents in a well-off area, and the wealth of the neighbourhood was worn by all of my peers. Once, I found a pair of red vintage Abercrombie shorts in the athletic wear section of Value Village, and even though they were itchy and weren’t exactly stylish, I begged my mom to buy them. When I wore them to school I would get complimented on them, only when my classmates were able to read the branding. For Christmas, in 4th grade, I was given a lime green Hollister hoodie. I wore it every day until it began to fray.

I don’t share these anecdotes to pity myself for my tax bracket or to sneer at the judgment from my classmates, but instead to analyze just how much fashion perception has changed over the past ten years. Most of the stores that dominated my childhood are currently struggling to barely stay afloat, with some even filing for bankruptcy. The same thrift stores that were once crowded with families in the same boat as mine are now also filled with the same broad range of crowds that used to frequent malls just as often back in the day. And, while some of my fellow “lower-class friends” have raised their concern with thrift stores becoming “mainstream”, I personally struggle to find anything to complain about. Sustainability doesn’t just have to be for those of us that grow up poorer, and at the end of the day, cheap clothes are a plus no matter who you may be.

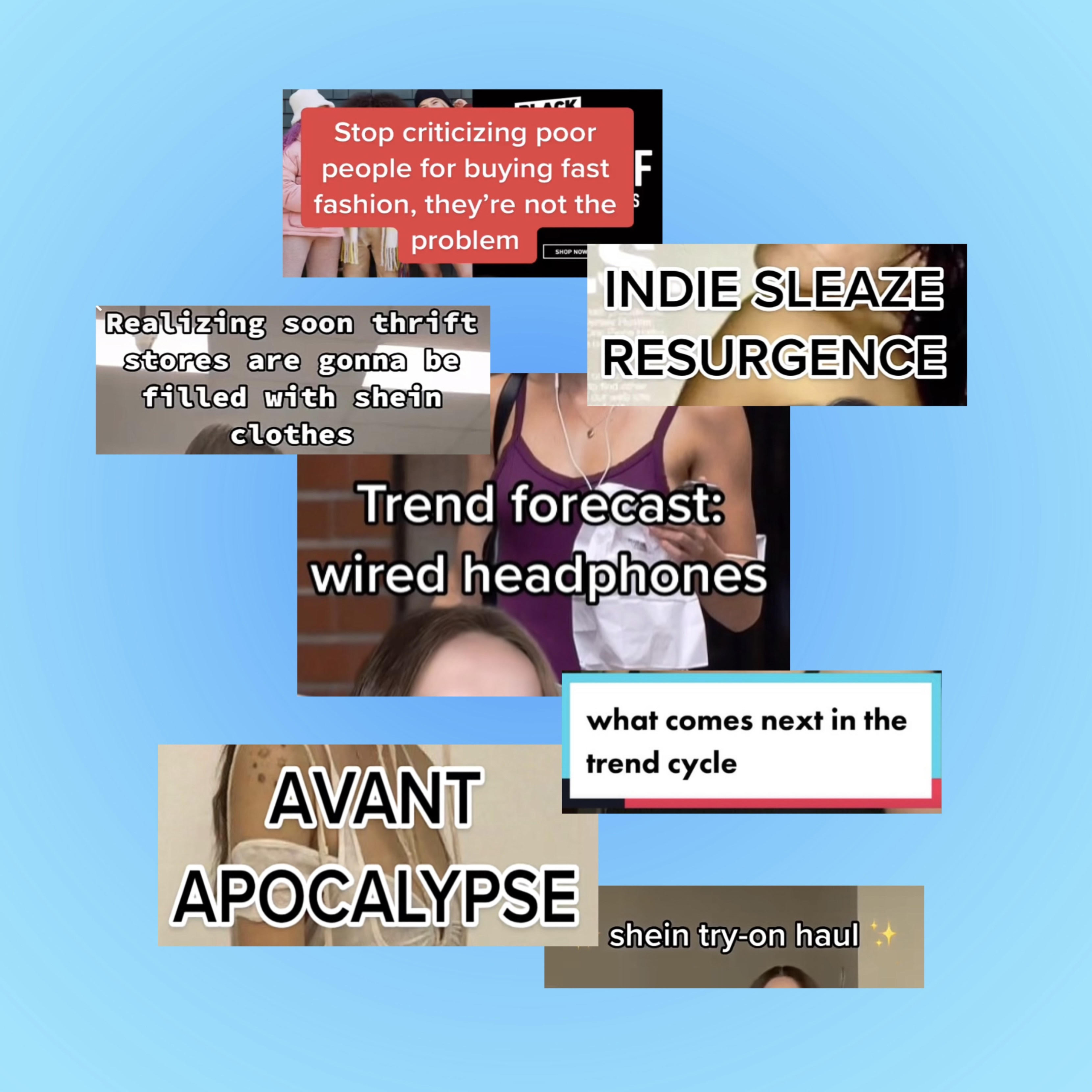

But the topic of sustainability in today’s day and age tends to raise more questions than answers. The concept of fast fashion is nothing new to the consumer market, yet we as a society have a better understanding of what goes on behind closed doors than ever before. The 2013 Dhaka factory collapse, the consumerist demand for ethically sourced clothing, the increase in thrifting, and the multiplication of fast-fashion conglomerates like SHEIN, Romwe, and FashionNova; today’s consumerist landscape is one of paradox and hypocrisy. Depop is littered with users reselling price-gauged thrift shop items for dozens more than their original second-hand price. When said users promote their sales on social media, they are often met with scrutiny, criticized for taking affordable clothing away from the lower-class individuals who may need it. On the same page, many on social media are also extremely critical of those who shop from fast-fashion brands, citing the low prices that these websites offer as only being possible due to the exploitation of workers in developing nations. A common counterargument is that fast fashion is necessary for those who cannot afford to buy new sustainably produced clothing. The blame shouldn’t be on the consumer, but on the industry as a whole.

With all of these comments and concerns, navigating the fashion landscape seems like a nearly impossible task for the average consumer. Thrifting should be encouraged due to its sustainability, but too much of it can raise prices, barring lower-income shoppers from being able to afford to buy second-hand. Buying fast fashion is unethical, but sustainably made, environmentally-friendly fashion is often significantly more expensive and harder to come by. Trend cycles shouldn’t be fed into, yet they continue to be ever-present regardless. So what are we as everyday consumers meant to do?

“I think that our generation has watched the impact that the internet has had on the trend cycle in real-time and it’s astonishing, to say the least,” Says Lis, a Toronto-based depop seller. Lis resells archive garments on her Instagram and Depop accounts, primarily sourced from designer collections from the early 2000s. Despite making her living on reselling items, Lis does not operate her depop store with the intention of capitalizing on current trends. “A lot of people feel the need to follow trend cycles and this contributes devastating effects on the climate as well as garment workers. Another group of people is fixated on “beating” the trend cycle by being ahead of it and forcibly disliking whatever is currently popular. These people feel a lot of superiority but they contribute to these issues in the exact same way. I don’t think a lot of people realize that we have gotten to the point where the cycle is so short that virtually anything can be considered a trend at any given moment.” Lis also grew up relying on thrift stores and developed her own personal style using the eclectic selection of items that thrift stores have to offer. However, Lis also recognizes the necessity that fast fashion holds for some people. “I don’t think people should be shamed for buying fast fashion, because it’s not an issue of individual actions. I think that secondhand options should be more encouraged and become more accessible. Everyone should have the right to have fun with clothes and be able to buy them, but the rights of garment workers to earn living wages are undeniably more important and people forget this”.

Chantal, a Toronto-based artist that creates and sells their own jewelry, is extremely critical of trend cycles. Childhood insecurity led Chantal to follow trends throughout their adolescence, but since high school, they have focused on developing their own personal style. “Sometimes fast fashion and trend cycles can make me so disinterested in fashion, the material consequences, lack of accessibility/affordability. Etc”. Like Lis, Chantal also recognizes how complex the world of sustainable fashion can be. “Whether we like it or not we are constantly consuming and producing and I just wish that people were more aware of the nuances to something as complex or simple as clothing to stay warm to the entire fashion industry”.

Despite Chantal, Lis, and I all having different relationships with fashion and different sartorial upbringings, we all have very similar perspectives towards sustainable fashion, despite none of our ideas addressing a true solution to the discourse. At the end of the day, there is no simple answer to an issue this nuanced and multi-layered, in which individual consumers have next to no power against international corporations. Tackling fast-fashion consumerism and overcoming trend cycles is as daunting of a concept as tackling late capitalism as a whole. It’s an undeniable uphill battle that is misunderstood by many. But merely the conversation behind sustainable fashion gaining traction in popular discourse is a step in the right direction. At this point in time, it seems the best way to conquer fast fashion and trend cycles is to unlearn the habits that capitalism has foisted upon us.

At the end of the day, fashion should not be a competition. The moment a form of expression becomes a battle of staying up-to-date and ‘fitting in’ is the moment that identity is lost. Brands and outlets will always attempt to push trends; it’s what ultimately keeps them relevant. Trend cycles were infinitely easier for advertisers to push in the time before social media, but today, any viral figure or highly-viewed video can influence a trend within a specific circle.

As Lis stated, the trend cycle has shifted. Alternative subcultures have been given the spotlight and the past ten decades have all been rediscovered at one time. This is a paradoxical time in which any given style could be seen as “in” or “out”, depending on who is judging. “I’m not concerned with whether I look “outdated” and I try my best not to be concerned with the things I like becoming “trendy”. Ultimately, now should be as good an opportunity as ever to embrace personal style, and gather pieces that you truly love, to build up a wardrobe to last for years to come, regardless of what’s plastered on Instagram advertisements and billboards at the mall. The most sustainable consumer is one who doesn’t overconsume at all. There is so much one can learn about not only their own personal taste but also their identity, the moment they stop falling victim to the blinding influence of capitalism.

Nicole Rayner is a Toronto-based writer and artist. She is currently studying media production and screenwriting at Ryerson University. Nicole has worked with organizations such as BetterHelp and Adolescent Magazine. She is very passionate about human behavior and pop-culture criticism.

Nicole Rayner is a Toronto-based writer and artist. She is currently studying media production and screenwriting at Ryerson University. Nicole has worked with organizations such as BetterHelp and Adolescent Magazine. She is very passionate about human behavior and pop-culture criticism.