Re-conceptualizing how public space is perceived today in tandem with how they are envisioned has to do not only with the future of a city but also with its past.

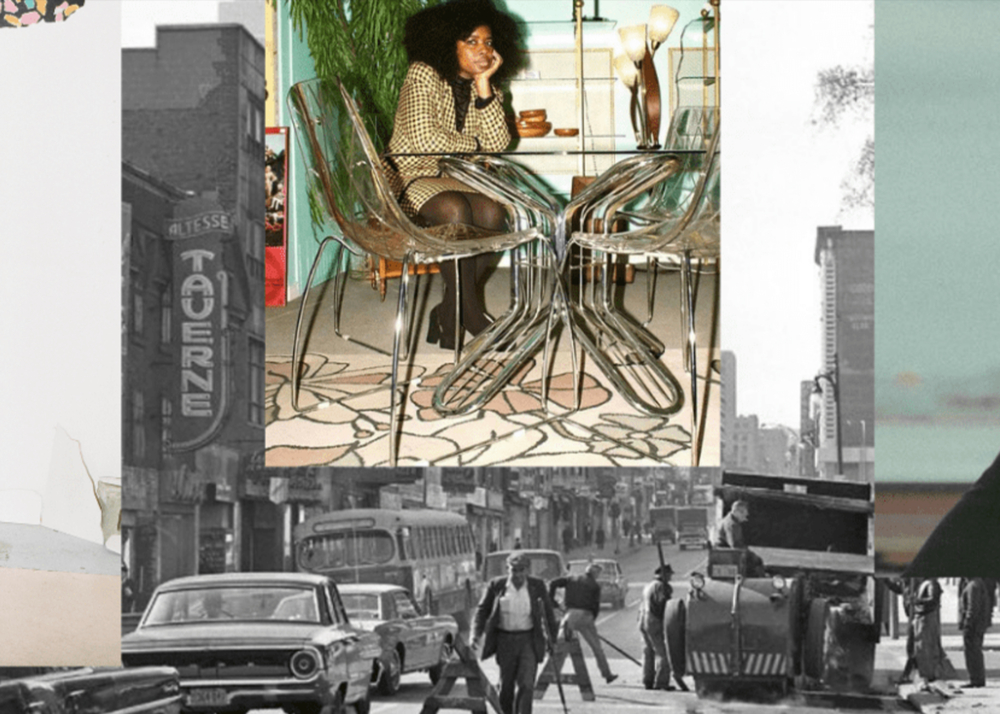

As public spaces reopen and restrictions are lifted, urban dwellers are enticed to revisit spaces where social interaction and new encounters are produced through the act of occupying a place. The pandemic brought on a dearth of these public spaces, which gave rise to a more digital and insular world. As a result, creative force and social mobility in digital spaces became integral in devising new ways of producing art that is accessible, provocative, and authentic. Moreover, entrepreneurialism further varied this mixture, with many of today’s creatives using Instagram and TikTok to garner success and promote their work. The post-pandemic milieu is burgeoning and has prompted a re-conceptualization of public space, one which speaks to the consumption of art and artistic production in physical space beyond the aforementioned digital ones. Evidenced by the ever-shifting contemporary art scene which now seeks to engage even more intimately with political discourse, there is a desire to not only witness but have a stake in creating change that may begin online, but demands physical social interaction. To help identify these shifts and influences, we spoke with three Montréal based artists who each engage with urban space and garner inspiration from the effervescent, contentious, and re-awakened urban environments around them.

Montréal has a past rooted in the reform of spaces and interest in developments as tools of attraction rather than community support.

Montréal has a history tied heavily to profit-oriented interests powered by corrupt mayors like Camillien Houde and Jean Drapeau. These same officials transformed the city into what may have been perceived globally as culturally and economically prosperous, but in reality, was lacking virtues and a concern for human scale. When reflecting on projects such as the urban renewal of Montréal’s entertainment district and slum clearance efforts, this becomes painfully evident; displacing sex workers and working-class women, and the infamous 1976 Olympic games which cost the provincial government over 1 billion dollars profited the city on a global scale, but on a human scale these efforts created much suffering. Montréal has a past rooted in the reform of spaces and interest in developments as tools of attraction rather than community support.

Artists are a powerhouse for communities in Montréal, enticing citizens to become active and engaged with their physical surroundings through acts of subversion and transformation. These forces work against government trends that seek outside attraction over local production and consumption. Meeting up in person shows officials that communities are not afraid to occupy space, combat profit-oriented reform, and devise bottom-up strategies to collaborate offline.

To help identify the intersections between the re-conceptualization of public space and the re-occupation of public places in Montréal, conversations with local creatives are crucial, enabling rhetoric that further universalizes an understanding grounded in how the history of a place and the occupation of public space imbues creative work. It is important to distinguish public space and place to better conceptualize how urban environments may be (re)democratized to better suit the needs of creative communities. The following definition is inspired by structuralist Marxist philosophers and geographers like Henri Lefebre and David Harvey.

“A place is an occupation of space. It is the afterthought of an already existing ground. Space is transient and mobile, a place is stagnant and may be monumental.”

“I love examining subcultures within a city. The way subcultures function in consciously developing their own norms and values relates closely to my relationship with society.“

Miranda Chan is a movement artist and dance director who has done extensive training in Montréal, having worked with Cirque du Soleil and the Montréal Symphony Orchestra. Recently she’s focused on applying her experience in directorial projects and passing on her skills to other creatives in Montréal.

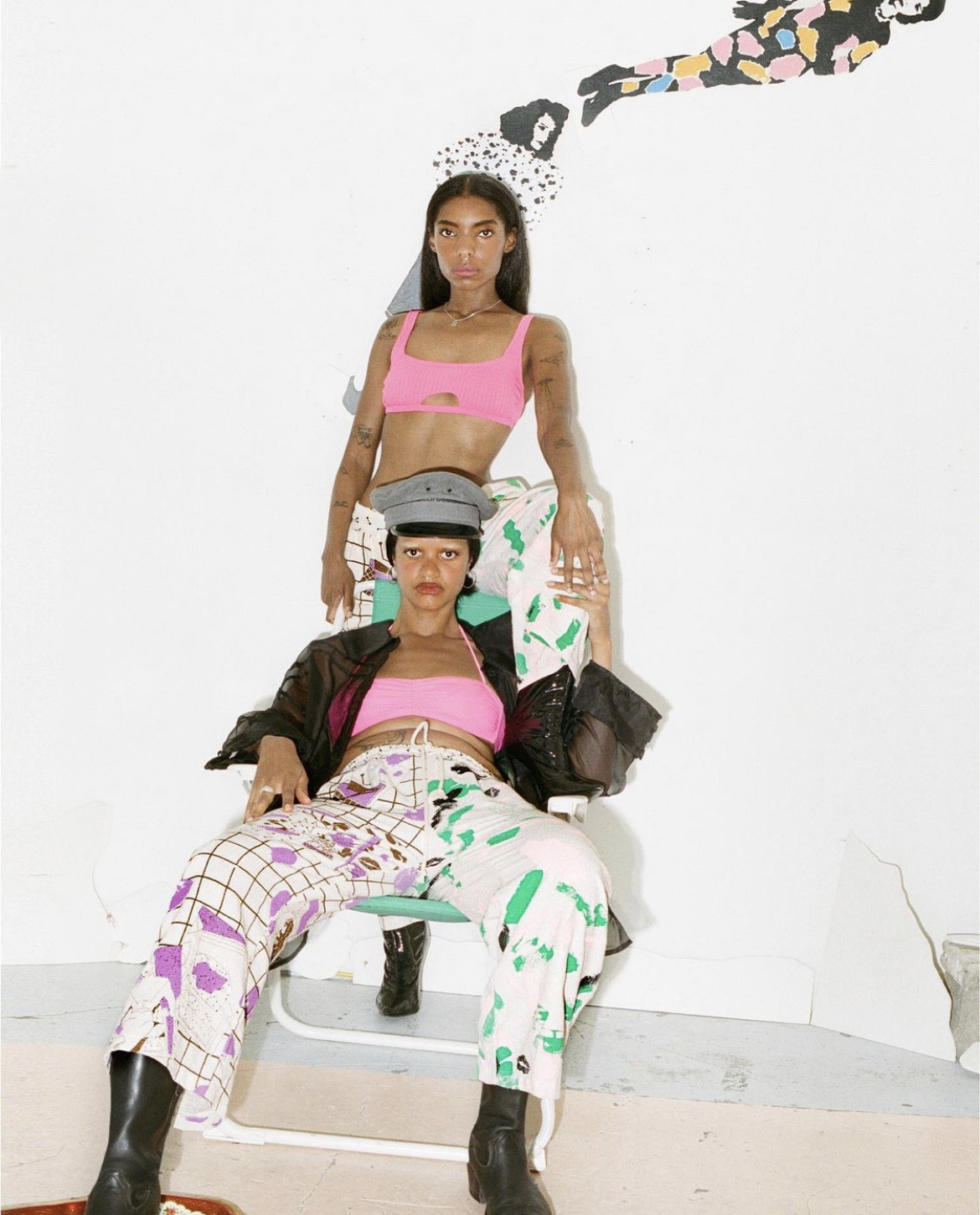

Kate Turner is a fashion designer who runs an online fashion line, combining authentic textures with hand-painted techniques to create comfortable casual wear for all sizes. Her work has gained immense recognition over the past year, with rising Instagram followers and prodigious collaborations, she is set to become the next household name in the Montréal fashion industry.

Magella is a DJ and musician who experiments with tone and self-describes her work as in one with the diasporic blues. She uses her voice as a brush painting sonic textures and hues to express themes related to isolation and resistance; two keywords that are unavoidable when caught daydreaming and reflecting on the past two years.

We asked Miranda, Kate, and Magella two questions to get a better understanding of how the city and its spatial atrophy impact their work.

Lucy: Artists are often cited as inspired by their environments, creating works that are a product of not only their internal thoughts and emotions but those witnessed around them. Does the city inspire your work? Are there certain spaces or aspects of the city’s history which you engage with during your creative process?

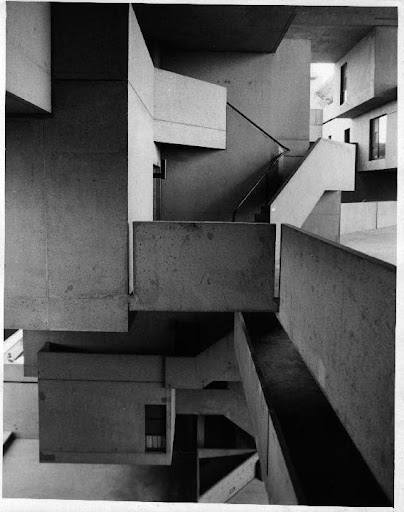

Miranda: I think it is important to look outside of ourselves for inspiration and to see what is happening in our environment in the present, politically and culturally. To go beyond us as individuals and to try to see what the collective is experiencing. I try to, through my work, make a comment on that by re-imagining what the future can look like or by re-imagining different ways of being than what society has decided as the status quo. We can change the way we as humans interact with each other and the environment completely through the way we mobilize around a city or how we build/ organize a city. An example is how the architect Safdie, in building Habitat 67, ensured that odd-numbered floors would be excluded from the elevator so that habitants would have to use the stairs, this promoted exercise and increased chances of habitants running into each other and creating interactions. He works by thinking of how form follows purpose in a way that goes beyond functionality.

An aspect of the city that inspires my work would be the public space that the people create for themselves and their communities as safe spaces that exist outside of what already is. That being said, I love examining subcultures within a city. The way subcultures function in consciously developing their own norms and values relates closely to my relationship with society.

Kate: Everyday Montrealers show up for each other in beautiful ways. To accept each other’s true selves or a version of that on our own paths. We show up and support each other’s expressions of our true selves expressed by fashion, queerness, art, and music. It is a beautiful thing to witness and inspires me every day. People are constantly testing their own boundaries and comfort with fashion in Montréal and I imagine those who buy my clothes feel it fills a specific niche of physical comfort first combined with a protective armour like edge to it. There is a true spirit of DIY culture in this city which I find endlessly motivating. This can be most seen in the Chabanel district which holds the cities dying (or reawakened?) garment manufacturing businesses.

Megella: My environment has an impact on what I create. I’ve always felt a sense of longing for this city. I record sounds (sometimes videos) wherever I am, whether on the metro or in any green space. My family immigrated to Montréal from Barbados and lived around the South West (Lasalle, Little Burgundy, and Verdun). While many have left over the years, there is still a sense of shared history. Since I moved back here for school, I actively try to connect childhood memories to different landmarks. I have memories of Caribbean grocery stores, churches, and outdoor places (Angrignon Park and the St. Lawrence River). My family would reminisce about both their artist and activist days here and lament on gentrification. This history has helped me hone my artistry and reinforce my sense of belonging to this city.

Lucy: Contemporary art has evolved to be more consumable outside of physical public space, and more so tied to virtual ones such as Instagram. How can we mobilize as local artists in the urban environment to work against this trend and to interact in public spaces?

Miranda: In Montréal when it comes to dance, they have created ways to democratize the audience more and for it to be accessible around the city. During the summer and into the autumn there are countless shows around the city. Re-imagining what a “stage” is and where art should be. Creating in-situ pieces and incorporating our environment as a dance partner, like something moving and alive, that energy flows through rather than something static. I would go further to re-imagining as stated above, how a city is built and organized in order to incorporate art and move beyond functionality.

Kate: I think we are seeing more and more designers welcoming patrons into their studio spaces both IRL and online to shop. This allows people to engage with your process as well as with the clothes, creating an extremely intimate experience that is not possible virtually. I don’t hide how my garments are made but include it as part of what the customer is buying. We can share as much as we want on Instagram but ultimately there has to be a moment or event or something special to share in person. I’d love to see more DIY fashion shows and open studios that provide those experiences.

Megella: The DIY scene is a perfect example of mobilization. While there is a natural exodus that occurs here every couple of years where people leave the city for new growth, there are still people who continue to cultivate the scene and create opportunities for emerging artists. A great example is the volunteer group Kickdrum who continue to use their platform to support emerging artists throughout the pandemic. Throughout the summer, they were hosting outdoor park shows around the city. While incorporating more well-known acts, they continued to include more emerging artists in their lineups. While we are in a time where art and virtual life are tied together, we need to remember that people still crave to see art in person; there is still a need to see live music. Another great highlight is how Pop Montreal handled their festival this year. Their focus was to include more local emerging talent in the line-up. While artists now have to include an algorithm as a potential roadblock, there are still ways for us to expand our reach and build communities for ourselves within our cities.

—combating contemporary forces of state-led initiatives such as displacement, and in turn, mobilizing as creative communities offline and in real life.

It takes a re-imagining of what we have been taught as normal to re-conceptualize a space, and inject a new collective value into a physical place —combating contemporary forces of state-led initiatives such as displacement, and in turn mobilizing as creative communities offline and in real life. Given recent affairs, the virtual connections made are vast. Magella, Kate, and Miranda are aware that their success depends on online spaces. The contingency of followers, friends, fans, and consumers produced online, however, may evolve to be more of a tool for mobilizing change in the physical spaces of the city —burdened by depressed sites and developments, they have the power to reinvigorate them as a collective.

There are still questions that linger on the topic, and we encourage you to reflect on them. We wonder about the accessibility of art as capital. With new trends such as the recent rise of NFTs, how can we mobilize for change in the less elite spheres of the art world? Can art consume a city? Has this happened in Montréal and does it have consequences?

~ Miranda Chan – https://www.miranda-chan.ca @itsmirandachan

~ Kate Turner – https://www.kateturner.ca @the.kate.turner

~ Magella – https://www.magella.xyz @magellaella

Lucy Earle is a freelance writer with an interdisciplinary background in urban studies and performance art.

Her work explores themes related to presence, public space, apparitions, and the grotesque. She goes by the pseudonym Shania Mark Twain to express her obsession with country-pop music and satire.